Bloomberg — In leafy Las Heras park near downtown Buenos Aires, young mothers push buggies in the late summer heat as locals sip maté in the shade. The scene would be typical of any middle-class neighborhood in a Latin American capital but for one thing: the moms are all speaking Russian. They’ve been arriving in Argentina in droves since Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine just over a year ago, many making the trip of more than 10,000 miles including layovers while heavily pregnant. Despite rolling economic crises and inflation near 100%, the country is providing a refuge from the war, a growing clampdown on dissent back home and the strict visa restrictions that have sprung up against Russians in other parts of the world.

One of the babies being pushed round the park is one-month old Lionel Zuev, whose parents arrived late last year, a few weeks before Argentina’s victory in the football World Cup. The infant, who became an Argentine citizen at birth, was named after Lionel Messi in a nod of gratitude to the country his mom and dad plan to make their home. As parents of an Argentine, they’ve already been granted residency and can apply for citizenship in two years.

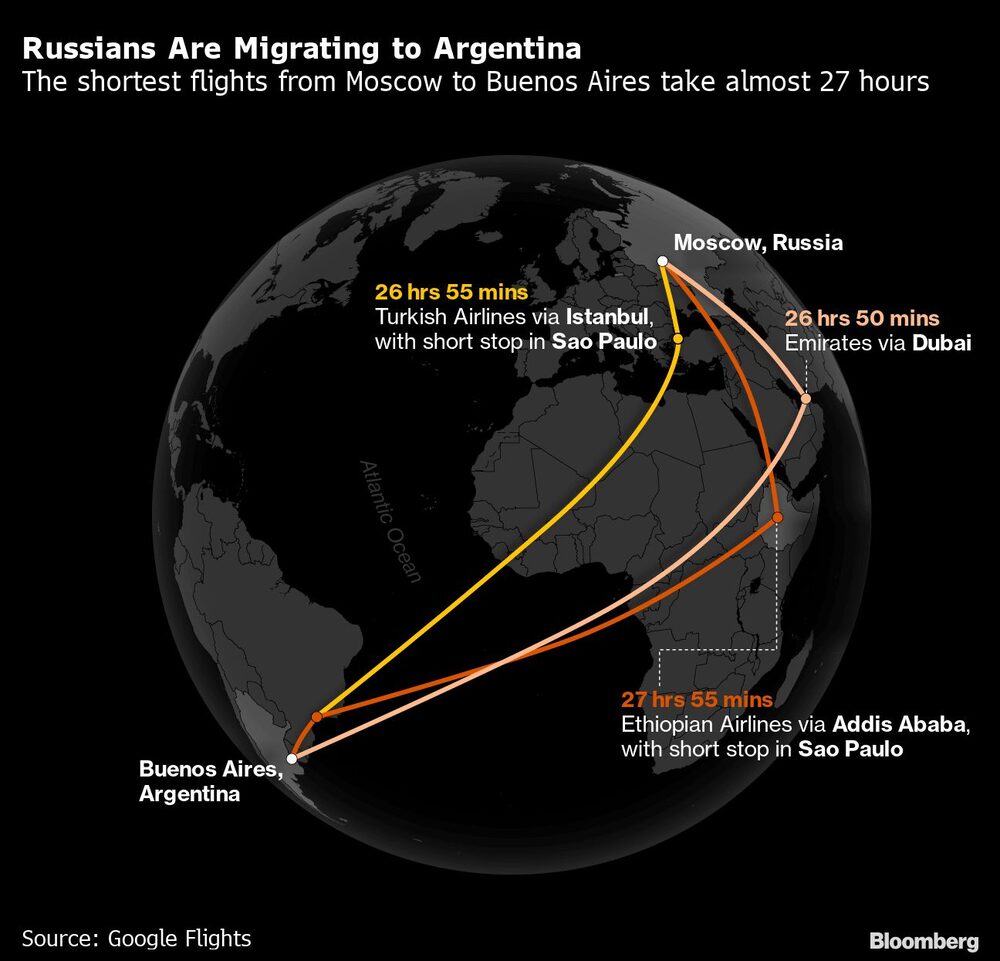

“We didn’t plan anything before November,” said Julia Zueva, 34. “I was in a group with different girls who were also pregnant, who all said ‘we’re flying to Argentina.’ I was interested to know why.”More than 22,000 Russians have entered Argentina since the start of last year, although around 60% of those have already left, according to Argentina’s immigration ministry. There is no data available on where they went. The largest surge took place in the fourth quarter of 2022. More than 4,500 Russians arrived in January, a fourfold increase from a year earlier, and in February, 33 women in their third trimester of pregnancy arrived on a single Ethiopian Airlines flight via Addis Ababa.

Brain Gain

The influx of mostly highly-skilled Russians could help Argentina plug a gap left by educated people moving to Europe in recent years to escape economic uncertainty. More than 32,800 Argentines arrived in Spain in 2021, the most since at least 2008, according to the latest available data from INE, Spain’s national statistics agency.

At the same time Russia’s economy is being depleted of talented workers in a brain drain comparable to the mass exodus following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. As many as 1 million people left last year, though some have since returned, most setting up new lives in places that have liberal visa regimes, such as parts of the former Soviet Union, the United Arab Emirates and Southeast Asia. Some have settled in other parts of Latin America, such as Brazil, according to local news reports.

The exodus may also be draining Russia of potential opposition to the Putin regime and the war in Ukraine. Most of the more than a dozen Russians in Buenos Aires spoken to by Bloomberg News were openly critical of the Russian leader. Hundreds of Russians and Ukrainians protested against the war in front of both nations’ embassies in Buenos Aires in February.

“It is the irony of exile,” said José Moya, a professor of history who teaches a course in global migration at Barnard College in New York. “By leaving, emigrants strengthen the tyrants that they’re against.”

Looking for Work

Many of the migrants seem unfazed by the uncertainty of living in a country that has defaulted on its sovereign debt nine times in its 200 year history. That’s partly because Russia has seen it’s own fair share of economic turbulence, but also because many of the arrivals have brought savings and remote work with them and so are initially cushioned against high inflation.

Victoria Bogataya, 35, arrived in January and is due to give birth later this month. She and her husband plan to stay and work in tourism, like they did back home in the Caucasus mountains in southern Russia. “I love Russia, but for the next decade, it looks like it’s going to get worse,” she said. “I want to give my daughter all the chances she deserves.”

Mark Boyarsky, 37, a freelance photographer, has already found work taking maternity pictures of newly-arrived Russian mothers. Currently he has demand for three to five photo sessions a week and usually receives payment in dollars. A transgender man, Boyarsky fled Russia with his wife and two children because of a 2020 constitutional amendment in Russia that outlawed same-sex marriage and banned transgender people from adopting children. They first went to Nepal before relocating to Argentina in September and applying for refugee status.

Others are still working out what to do, having left Russia in a hurry and without a plan. Alex Shemiakin, 37, quit his job as an engineer to make the move with his wife to avoid the possibility of being drafted to fight in the war. He says he never wants to go back.

“At home I had three options: leave, keep my mouth shut and get drafted, or speak against the war and get thrown in prison, and then get sent into war anyway,” Shemiakin said, while chatting in English over beers following a Russian-language pub trivia evening at a bar next to Las Heras park. “I was tired of my uncle calling me a traitor for opposing the war.”

Well-Trodden Path

Argentina, once among the wealthiest countries in the world enshrined an open immigration policy in its 1853 Constitution and became a popular destination for Europeans fleeing famine, persecution and war early in the 20th century. Those arrivals — many of them literate, skilled laborers — settled in Argentina because wages were higher than back home, and because there were economic opportunities in the nation’s vast grains-producing Pampas region.

The US and Europe have made their immigration policies increasingly restrictive since the 1950s, yet Argentina has remained relatively accessible, according to Benjamin Bryce, an associate professor of history at the University of British Columbia, who focuses on migration in the Latin American country. Russians who aren’t planning to have a baby can enter the country on a three-month tourist visa and then apply for a student or digital nomad visa while in the country. The government has welcomed the Russian arrivals who plan to stay, while opening an investigation into those who give birth just for the passport and then leave.

Although international air travel has made the journey from Europe easier than for previous generations, sanctions have added new hurdles for the current cohort. With direct flights from Russia to most European nations no longer an option, many migrants reach Buenos Aires via circuitous routes involving multiple layovers. The fastest routes via Istanbul, Addis Ababa and Dubai cost upwards of $1,500 for a one-way ticket.

Restrictions on Russian banks have made credit and debit cards unusable overseas leaving little option than to carry as much cash as possible on the journey and then transfer savings and earnings via cryptocurrencies or wire services via bank accounts held in former-Soviet republics. Avoiding normal channels does have its advantages as it allows the new arrivals to skirt Argentina’s capital controls and receive pesos at a parallel exchange rate that’s nearly double the official rate.

A small industry has grown up to take advantage of the growing demand for information about relocating to Argentina. A criminal group that was providing Russians with fake documents was shut down following a police probe in February, but other more legitimate organizations are also offering advice and help on dealing with bureaucracy and finding somewhere to live.

Most people are getting and sharing information on Telegram, a messenger service popular in Russia. One channel that provides advice on everything from finding a good hospital for giving birth to how to exchange money on Argentina’s widespread black market has more than 10,600 subscribers.

Back in Las Heras park, Russian families bask in the Southern Hemisphere summer, strolling among the pink blooms of the palo borracho trees. Zueva, the mother of baby Lionel, says that many Russians are attracted to Argentina because, half a world away from the conflict in Ukraine, they can live free of judgement about Putin’s aggression.

“This country isn’t negative toward Russians, like in the US for example,” Zueva said. “It doesn’t matter where you came from, you can live here like a local.”

--With assistance from Hayley Warren, Patrick Gillespie and Andrew Rosati

Read more on Bloomberg.com