Bloomberg — Colombia’s first leftist president starts his four-year term on Sunday, inheriting shaky public finances that will make it tough for him to deliver the lavish social programs his supporters expect.

Gustavo Petro assumes control of an economy with government debt near record levels, forcing him to make some difficult choices between meeting his promises and preventing the fiscal deficit from ballooning out of control.

In the first big test of Petro’s ability to govern, his finance chief Jose Antonio Ocampo has said he’ll send a tax reform to congress as soon as Monday. The bill will be a gauge of Petro’s support among lawmakers, and will also determine if he’ll be able to boost spending on welfare and infrastructure, or whether a lack of money will derail his plans.

“The economic situation is not the most conducive to embarking on an ambitious agenda to expand public spending,” said Jose Ignacio Lopez, head of research at Bogota-based investment bank Corficolombiana.

Petro, 62, defeated a construction magnate in the June presidential election, to become the first leftist to win power in a country that has only ever been run by conservatives and liberals. With his victory, Colombia joins the ranks of nations worldwide that have voted in anti-establishment leaders recently. In Peru, a school teacher from a Marxist party became president last year, while Chile elected a former student protest leader.

The country’s first Black vice president, Francia Marquez will also be sworn in alongside Petro.

Petro, an ex-guerrilla and former Mayor of Bogota has pledged to tax big landowners, halt the awarding of oil exploration licenses and to rebuild diplomatic relations with the socialist government of neighboring Venezuela.

While diplomatic ties between the two nations were severed in 2019 amid a push by Colombia and the US to force out the socialist government of Nicolas Maduro, Petro has vowed to re-establish ties and open the border for commerce. A concert is planned Sunday on a bridge connecting the countries to celebrate improving relations.

Petro’s election may also shake up relations with Washington in a country that has for decades been the region’s strongest US ally. President Joe Biden and Petro have already spoken by phone and even before the inauguration, the US sent a delegation last month to meet in Bogota in a sign that the US wants to maintain its strong ties with the Andean nation.

Heads of State including Chile’s Gabriel Boric and Argentina’s Alberto Fernandez are set to attend the swearing in ceremony in Bogota. Maduro couldn’t attend, because outgoing President Ivan Duque says he’s a dictator, and barred him from entering Colombia.

Tax the Rich

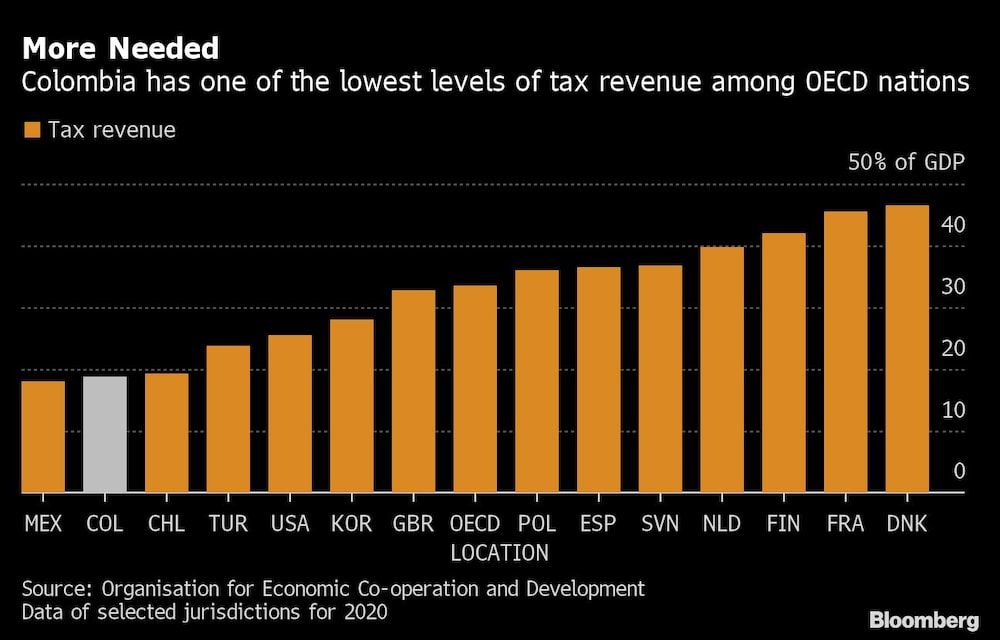

During the campaign, Petro said he could raise taxes on the rich by enough to both fund social spending and cut debt, but no government in Colombia’s recent history has achieved anything remotely as ambitious as his proposal.

Petro said that his bill will seek to raise revenue by the equivalent of about 5% of gross domestic product, by eliminating tax breaks and imposing a wealth tax, among other measures.

Since 1995, the country has passed fourteen tax bills, none of which raised more than 2% of GDP, according to Credicorp Capital Research. The fiscal deficit this year, adjusted to include gasoline subsidies, is forecast to be about 7% of GDP.

Even after successfully reaching alliances with several parties in congress, Petro will probably manage to raise less than half of the sum he aspired to, Lopez said.

Incoming finance minister Ocampo said the government may shoot for an initial revenue boost of closer to 2% of GDP, then gradually increase this with measures such as a crackdown on evasion.

Last year Colombia lost its investment grade credit rating, after mass protests led the government to water down a plan to raise taxes to fund pandemic spending. Government debt dropped slightly in 2021, after reaching a record high of 66% of GDP the previous year.

On the bright side, the economy will expand 6.9% this year, according to the central bank’s forecast, outpacing Brazil, Mexico, Peru and Chile, which should improve public finances.

Another Headache

Another headache for Petro is the vast sums the nation is now spending on fuel subsidies. Rather than allow gasoline prices to rise in line with crude this year, the Duque government capped the increases.

At current prices, that will cost the Treasury the equivalent of more than 2.5% this year. Petro can either bite the bullet and gradually allow them to rise, which would be unpopular and would make the highest inflation rate in 23 years even higher. Or he can continue to spend a big chunk of his budget on a subsidy that mainly benefits the wealthiest Colombians.

The peso is the worst-performing currency among major emerging markets since Petro won the election, and last month reached a record low against the dollar. But his appointment of Ocampo, one of Colombia’s best-known economists, calmed some investors, who took it a signal that he’ll eschew extremism.

Colombia’s “unsustainable” finances mean that the new government will have to “postpone many of the campaign promises that mean more spending, and give priority to reducing the fiscal deficit,” former Finance Minister Mauricio Cardenas wrote in a statement he posted on Twitter.

Investors are already taking their money out of emerging markets, and Colombia can’t afford to risk a sudden exodus of capital, he wrote.

Read more at Bloomberg.com