The fight against corruption is not a priority for Latin American governments, amid the ravages left by the Covid-19 pandemic and economic problems such as high inflation, warned the Council of the Americas and Control Risks in their report that evaluates and ranks 15 countries in the region.

However, despite the fact that governments have opted to relegate anti-corruption reforms and that the reality varies in each of the countries, the scenario in 2022 is one of “relative stability” after years of setbacks, according to the report.

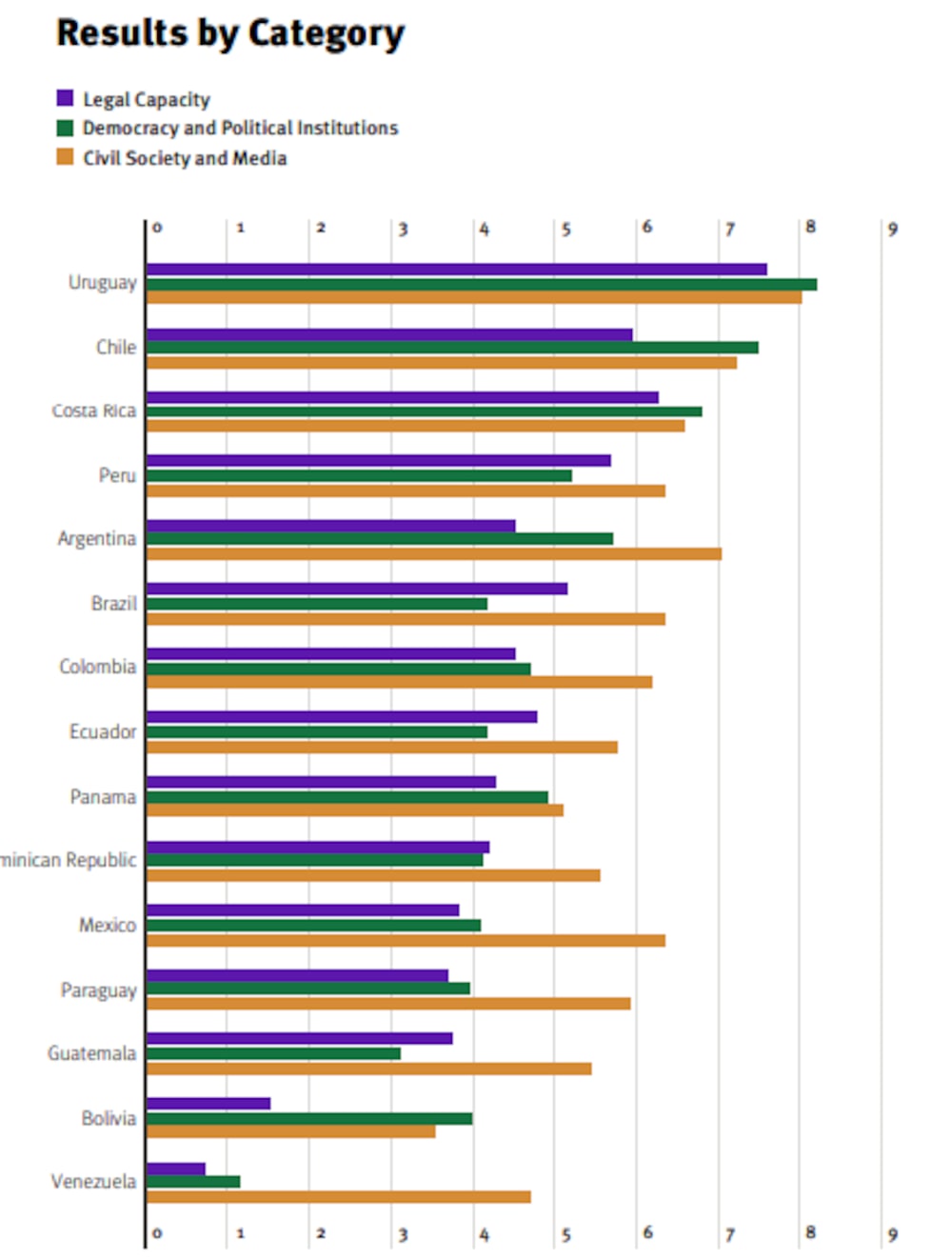

Uruguay once again leads the Latin American ranking for Capacity to Combat Corruption (CCC), despite the fact its overall score this year dropped from 7.80 to 7.42. The drop, the report explained, is due to variables that measure the level of international cooperation, the effectiveness of anti-corruption agencies, and the country’s capacity to combat white-collar crime.

Despite this, the document highlights that Uruguay outperforms the region’s average “thanks to its independent institutions, active civil society and solid democratic credentials”.

Costa Rica is in second place in the ranking, with a score of 7.11, while in third place is Chile, with 6.88 points.

While Venezuela appears at the bottom, Guatemala, Mexico, Brazil and Argentina have showed the greatest setbacks in 2022, compared with the previous year’s ranking.

Changes in second and third place

In addition to Uruguay’s leadership, a position it maintains for the third consecutive year, the authors of the ranking highlighted the strong performance of Costa Rica and Chile.

Costa Rica’s score rose 10% over the previous year, due to a “moderate improvement” achieved by measures such as the launch of the National Integrity and Corruption Strategy, and investigations into alleged corruption schemes between construction companies and public officials. Those advances allowed Costa Rica to reach second place in the ranking for the first time.

Regarding Chile, the report highlights a 5% increase in its score due to aspects such as the independence and effectiveness of anti-corruption agencies, the mobilization of civil society, the investigation of alleged crimes in the army and accusations against former president Sebastián Piñera after the leak of the Pandora Papers.

“In April, the Constitutional Convention approved 10 articles related to probity, transparency and accountability. President Gabriel Boric, in office since March, has announced an ambitious set of reforms, including an anti-corruption and probity agenda,” the report adds.

Peru was ranked fourth.

The document also highlights that, within the lowest-ranked countries, there have been some signs of improvement.

Venezuela, although it remains in last place and is far behind the rest of the countries in the region, has shown progress in the category of digital communications and social networks, due to “the growing diversity and sophistication of digital media that continue to denounce state corruption”, the report states.

Bolivia also made “modest progress” in the categories of legal capacity and civil society and media, although it only managed to surpass Venezuela in the overall ranking.

The report says that there are problems in the country, citing the fact that “the use of justice for political motives has continued during the mandate of President Luis Arce” as an example.

The analysts note that Guatemala experienced the largest decline in terms of score, but that there were also declines in the three major economies in the region: Brazil, Mexico and Argentina.

These three countries have shown declines in each of the three editions of the ranking.

In the introduction to the report, the authors state that “some countries showed resilience, while others, including the region’s two largest countries, Mexico and Brazil, suffered further setbacks in key institutions and in the anti-corruption environment as a whole.”

Methodology

Published for the first time in 2019, the index assesses the countries’ anti-corruption capacity. Those conducting the survey highlight that, rather than measuring perceived levels, the Index assesses and ranks countries based on how effectively they fight corruption.

Countries with a higher score are considered more likely to have corrupt actors prosecuted and sanctioned. Continued impunity is more likely in countries at the lower end of the scale.

Here are some of the findings for the region’s five largest economies:

Brazil

Brazil dropped in the Index for the third consecutive year, falling from sixth place in 2021 to 10th place in 2022. Its overall score is down 6% since last year, and has fallen 22% since 2019.

The report points out that in the region’s leading economy, the Supreme Court and the Supreme Electoral Court remain independent from the government, despite President Jair Bolsonaro’s escalating public criticism of them.

However, the variable that evaluates the independence and effectiveness of anti-corruption agencies fell by almost 19%, as “Bolsonaro has sought to consolidate control over agencies that investigate alleged corruption involving his allies”.

Mexico

Mexico, the region’s second-largest economy, fell from 11th to 12th place in the ranking, and its overall score continued on a downward trajectory, dropping nearly 5% in 2022 compared with the previous year, and 13% from 2019.

The country experienced setbacks in all categories, but the steepest decline was in democracy and political institutions. In that category, Mexico had a sharp drop in the variable that evaluates legislative and government processes, “reflecting perceived efforts by the executive branch to interfere in legislative and judicial affairs”, the analysts explained.

Argentina

With the third largest GDP in Latin America, Argentina’s overall score declined by 2%, leading it to fall from fifth to sixth place in the 2022 rankings.

Argentina recorded slight improvements in all categories, except in legal capacity, which declined by 8%. Its score for the independence and efficiency of anti-corruption agencies fell for the third consecutive year.

Colombia

Despite a small improvement in its overall score, Colombia fell from seventh to eighth place in the Index.

The country, which boasts the region’s fourth-largest GDP, advanced slightly in the civil society and media and legal capacity categories, but fell by 6% in the democracy and political institutions category, maintaining a downward trend in that category since 2019, and falling behind the regional average.

Chile

Chile’s overall score increased by 5%, but its upward trajectory did not maintain the same pace as Costa Rica’s, leading it to drop from second place in 2021 to third place in 2022.

The country maintained its third position in the legal capacity category, which saw an 8% increase in score over the previous year, bolstered by improvements in key variables assessing the level of international law enforcement cooperation and the independence and effectiveness of anti-corruption agencies.

As in 2021, Chile outperformed the regional average in almost all variables analyzed.

Translated from the Spanish by Adam Critchley