Bloomberg Opinion — Taking to the radio to announce the nationalization of Mexico’s oil and gas, on March 18 of 1938 President Lazaro Cardenas enumerated the risks Mexico faced if the foreigners that controlled this vital resource somehow curtailed its supply. “The very existence of government would be endangered” he intoned. “Political power would be lost, bringing about chaos.”

That oil and gas still exert such a totemic power over Mexican politics more than eight decades later explains the peculiar, Back-to-the-Future nature of the presidency of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador. Often seen as a left-wing populist, he is, rather, a staunch conservative, anchored to a decades-old vision of Mexico that encompasses everything from natural resources and the environment to the exercise of presidential power.

It shouldn’t be surprising that this mindset is giving foreign companies a hard time. What is most unfortunate is that it also endangers Mexico’s prosperity, putting at risk its ability to engage with the global economy.

Last week, the Biden administration initiated a trade dispute against Mexico for favoring the state-owned oil and power companies at the expense of American energy firms.

“Mexico has pursued an energy policy centered on reinstating the primacy of its state-owned electrical utility, CFE, and oil and gas company, [Petroleos Mexicanos],” the United States Trade Representative complained.

It accused Mexico of amending its power law to give priority to electricity produced by the CFE over the usually cheaper and cleaner power produced by private, often American, rivals. It griped that Pemex was exempted from some pollution rules. It complained that the Mexican government has been denying and delaying permits, and even revoking licenses already awarded to private energy firms.

The USTR argued that these actions represent a breach of the USMCA, the trade agreement signed in 2018 between the two countries and Canada. It also pointed out that the moves will complicate Mexico’s ability to meet the climate goals it set under the Paris Agreement.

AMLO, as the Mexican president is known, is outright messing with North America’s competitiveness, it said: “To reach our shared regional economic and development goals and climate goals, current and future supply chains need clean, reliable, and affordable energy.” Mexico is putting that objective at risk.

Canada agreed, immediately pursuing a complaint of its own. Yet even as lawyers and negotiators saddle up, their legal arguments will have a hard time overcoming Lopez Obrador’s belief that he is returning Mexico to the virtuous path that fulfills its manifest destiny – articulated by Cardenas almost a century ago.

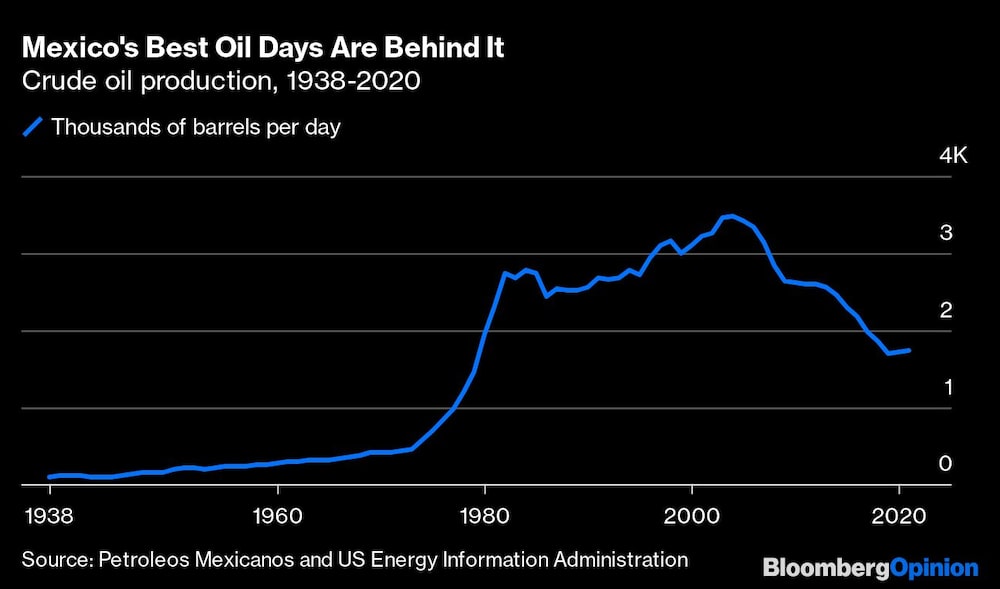

Lopez Obrador was born 15 years after General Cárdenas’ speech, in the Macuspana region of the state of Tabasco, where British companies had been pumping oil since the early 1900s. By the time he entered politics in the mid-1970s Mexico was awash in oil and gas, producing ten times as much as in 1938. Almost 60% of it came from Lopez Obrador’s home state.

In Mexico, it’s always fun to poke gringos in the eye. During his regular press conference on July 20, Lopez Obrador took a dig at the USTR playing “Uy, Que Miedo,” roughly “Ooo I’m so scared,” by the 1970s tropical songster from Tabasco, Chico Che. “We are very worried,” the president noted, somewhat sarcastically. “Nothing is going to happen.”

But more seriously, Lopez Obrador stressed that he demanded the overhaul of the energy clause in the 2018 trade agreement negotiated by his predecessor, Enrique Pena Nieto, forcing the US and Canada to acknowledge “the nation’s dominion over energy policy.”

He asked the gathered Mexican journalists: “How would we compromise our sovereignty?”

This is not capricious. Nor should it be discounted as a standard gambit of the old Latin American left, which has tended to view private capital, especially foreign private capital, as inherently corrupt.

The president is not some caricature of old Cold War tropes. His world view stems from a deeply idiosyncratic understanding of where Mexico went wrong, steeped in the logic of energy.

By his reckoning, that happened a half-century ago.

In the mid-1970s Mexico’s hydrocarbon reserves were 12.5 times what they were in the day of Lazaro Cardenas – worth 30 years of production at the then-going rate. Mexico was self-sufficient not only in gasoline but also in most liquid fuels, as well as natural gas.

Mexico, in Lopez Obrador’s view, was also better back then in other ways. It was not yet polluted by the neoliberalism of the 1980s, which produced a morally dubious, “aspiracionalist” urban middle class in the president’s words: “very individualistic, very selfish, very focused or oriented toward material progress.”

It was a time when import-substitution anchored Mexico’s economic strategy, before technocrats embraced globalization and tried to hitch Mexico to multinational value chains. It was a time when The State – in the form of an all-powerful president – determined the nation’s development priorities.

Lopez Obrador’s draconian macroeconomics draw inspiration from 1976. (Despite being hammered by Covid-19, Mexico in 2022 had what the International Monetary Fund pegged as the world’s second tightest budget.) That was the year when fiscal profligacy brought about a mega-devaluation of the peso that ended 20 years of macro-stability, plunging the country into an economic and political crisis.

His project is to return Mexico to the moment before this day. The Fourth Transformation, as Lopez Obrador calls his political project, is in this sense not a progressive endeavor but perhaps the most conservative turn in Mexico’s history since the revolution in the early 20th century.

Gazing ahead, into those days when Mexico was self-sufficient in energy half a century ago, he does not flinch at raising Pemex’s budget to $32 billion in 2022 – or 17% more than last year – to try to halt the near two-decade fall in oil production and redouble the nation’s capacity to refine gasoline.

The real future, the one that lies in the days ahead, has a harder time drawing his attention.

A study published earlier this year by the United States’ National Renewable Energy Laboratory concluded that Mexico is within reach of its target of raising the share of power from clean sources to 35% in 2024, up from about 27% in 2021. It could do so while cutting Mexico’s power bill by $1.1 billion compared to a business-as-usual path.

Mexico is moving in a different direction, though. Another NREL report estimated that prioritizing power supplied by the CFE – dependent as it is on dirty gas-oil – could raise power prices by up to 52% and increase CO2 emissions by up to 73 million tons from current levels.

The leader of a country that long ago abandoned import substitution, relying on exports for 40% of its gross domestic product in 2021, might care about the consequences of forcing its companies to foot a higher energy bill for dirtier energy.

This Mexican president has his sights elsewhere. Mexico is one of the only economies in Latin America not to have recovered its level of output before the pandemic hit.

The nation is likely to be in worse shape when Lopez Obrador’s term ends – poorer; less connected to the world – than when it began “On present trends, average income per capital in 2024 will be lower than in 2019, and the number of people living in poverty higher,” noted Santiago Levy, a Mexican economist and former head of the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association who declined Lopez Obrador’s invitation to become his first finance minister.

Chalk that up to searching for Mexico’s future in the past.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Eduardo Porter is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Latin America, US economic policy and immigration. He is the author of “American Poison: How Racial Hostility Destroyed Our Promise” and “The Price of Everything: Finding Method in the Madness of What Things Cost.”