Bloomberg — The warning signs are out there: In the absence of affirmative action, Black, Hispanic and Native American students are largely and disproportionately kept out of the best US schools — and the best jobs.

When the practice ended in California, the state’s most selective campuses saw minority enrollment drop more than 50%, and earnings fall for Black and Hispanic graduates. University of Michigan still hasn’t fully regained its share of Black students, despite millions of dollars spent over 15 years. And at the University of Oklahoma’s largest campus, the number of Indigenous freshmen fell 11% in one year, despite the state being home to one of the largest Native American populations.

Should the US Supreme Court do away with affirmative action, as it’s considering in two cases Monday, the most elite institutions in the US will almost certainly become Whiter in a country where social mobility for some racial and ethnic groups is already a challenge.

Minority college enrollment has overall grown, and will continue to do so as the country’s demographics shift. But banning race-conscious admissions will alter who gets into the most selective schools that not only set young adults up for future success, but often determine who fills C-suites, the halls of Congress, and even the Supreme Court bench itself.

Nearly 70 major US companies, including Alphabet Inc.’s Google, General Electric Co., and JetBlue Airways Corp. warned in a brief to the court that without affirmative action they’ll lose access to “a pipeline of highly qualified future workers and business leaders” — and will struggle to meet diversity hiring goals they’ve set.

“This matters a great deal for access in the persistently White institutions that generally control the pathways to power in our society,” said Ed Wingenbach, president of Hampshire College, a liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts.

The cases — one centered on Harvard and another on the University of North Carolina — could scrap the decades-old precedents that maintain the rights of public and private universities to consider race in admissions to ensure campus diversity. The challenger, an interest group set up to abolish race-conscious admissions, argues that Asian Americans are discriminated against due to such policies.

Institutions of higher education in the US first adopted affirmative action during the civil rights era to remedy racial discrimination and bias that kept non-White people, particularly African Americans, out of positions of power and well-paying jobs. In the decades since, the court has put guardrails on the ways in which schools can consider race in admissions, but has continued to allow schools to do so.

The vast majority of colleges and universities in the US now use what’s called a “holistic” admissions process. Schools consider a number of factors like extracurriculars and life circumstances, including racial background and socioeconomic status, in addition to academic performance, when deciding who to admit.

Under that current system, most schools have improved representation of admits and graduates. In a McKinsey & Co. analysis of 840 four-year institutions, almost two-thirds increased representation of minorities within their student bodies between 2013 to 2020. More than 50% had also improved graduation rates for minorities.

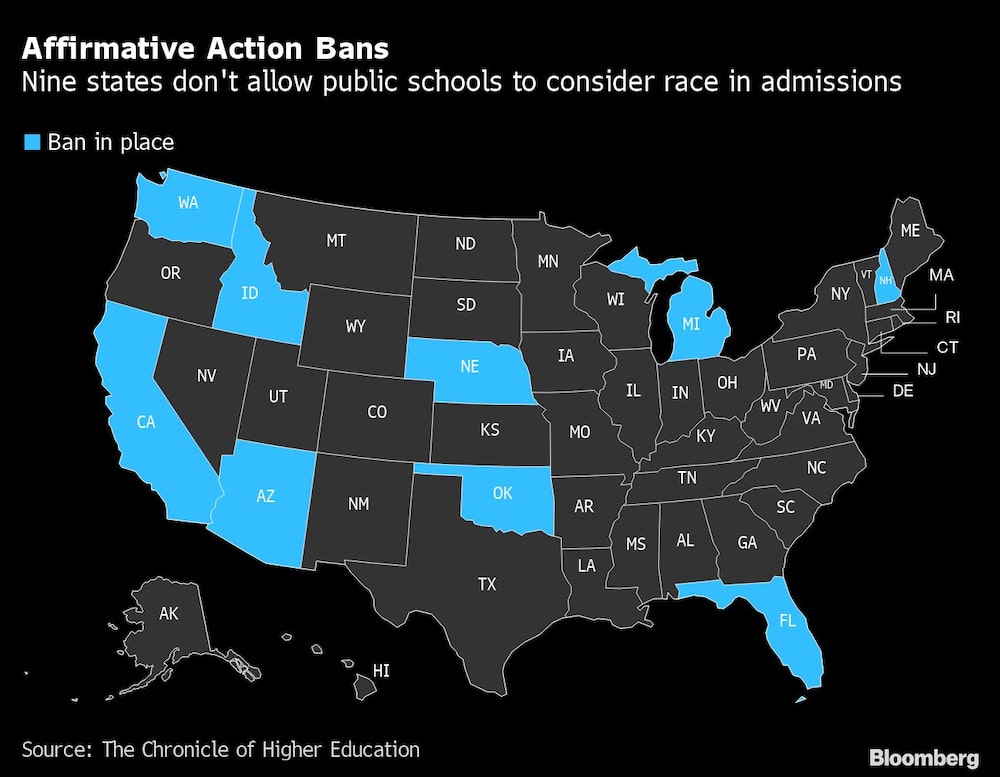

But nine US states currently ban affirmative action in public school admissions. In those places, the racial makeup at the top-rated schools has changed dramatically.

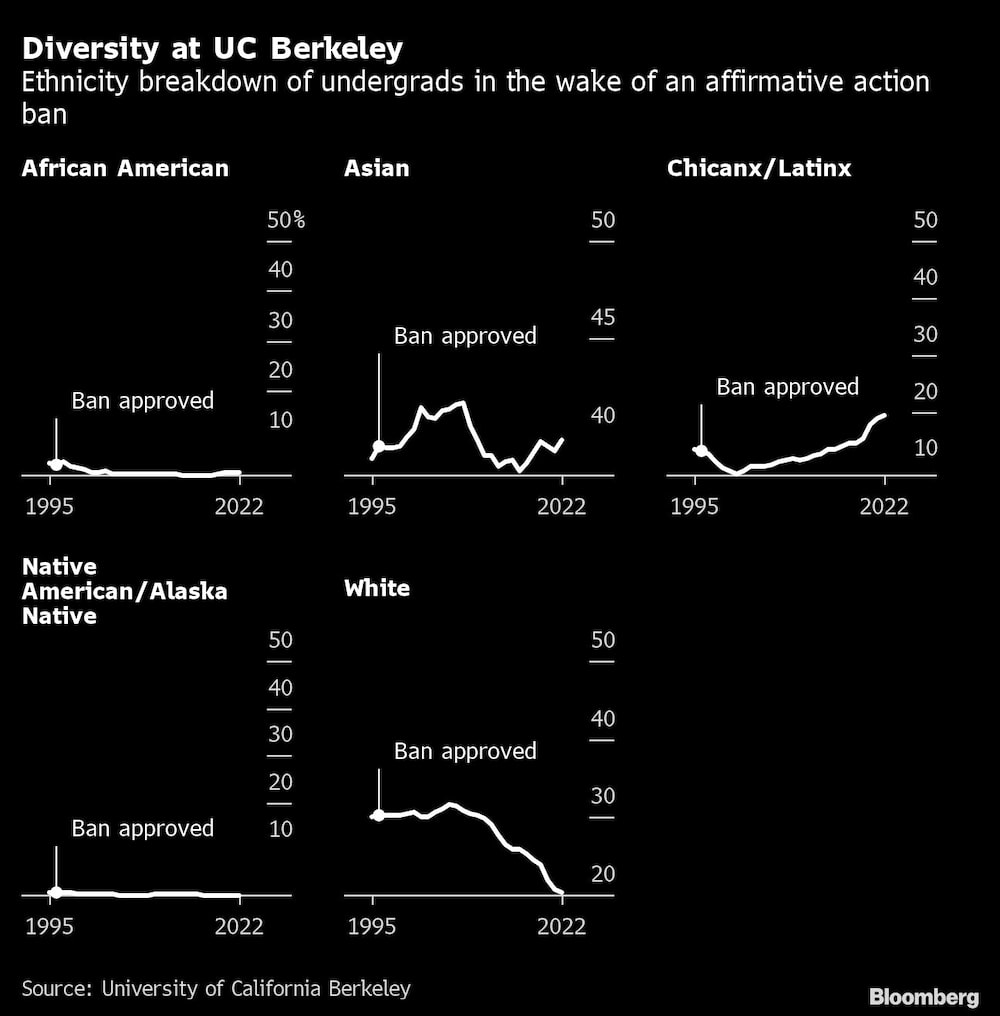

After California’s ballot measure banning affirmative action went into effect for the freshman class of 1998, freshmen enrollees from underrepresented minority groups dropped by 50% or more at the the University of California’s most selective campuses, the school’s president and chancellors said in a brief to the Supreme Court.

At UCLA, the share of Black freshmen halved from 7.1% in 1995 to 3.4% in 1998, the chancellors said. Latinx students accounted for 22% of the freshman class in 1995 but only 10% in 1998. The share of African American freshman at UCLA, at 6%, is still below its pre-ban level.

UC Berkeley saw a similar drop: Black students comprised 3.4% of the freshman class in 1998, down from 6.3% in 1995. The share of Latinx freshman dropped to 7.3% from 16% in that time.

“Black and Hispanic populations in the selective universities collapsed,” said Zachary Bleemer, an assistant professor of economics at the Yale School of Management who’s studied the impact the affirmative action ban had on minority students.

Bleemer’s research found that the change hurt long-term earnings for Black and Hispanic graduates, too. A decade after the University of California system ended the practice, minority Californians earning over $100,000 declined by at least 3%, according to his analysis of 10,000 UC freshman applicants. And overall, Black and Hispanic college applicants were earning about 5% lower wages than they would have absent the ban. White and Asian graduates’ earnings during that time, on the other hand, saw little benefit from getting rid of race-based admissions, the research found.

Opponents of affirmative action point out that both UC Berkeley and UCLA admitted their most ethnically diverse classes in recent years. But the campuses’ demographics do not reflect that of the state’s high school graduates. Just 19% of Berkeley’s student body identifies as Latinx, while the numbers of Hispanic or Latino public high school students in California has soared to more than half. For Black students, the numbers are slightly better: 5.2% of high school students are Black, compared to 3.8% of UC Berkeley’s students.

Meanwhile, the Asian student makeup at Berkeley hasn’t changed much since the ban, continuing to hover around 40%. The share of White Berkeley students has gone down, but in line with the overall decline in White high school graduates in the state.

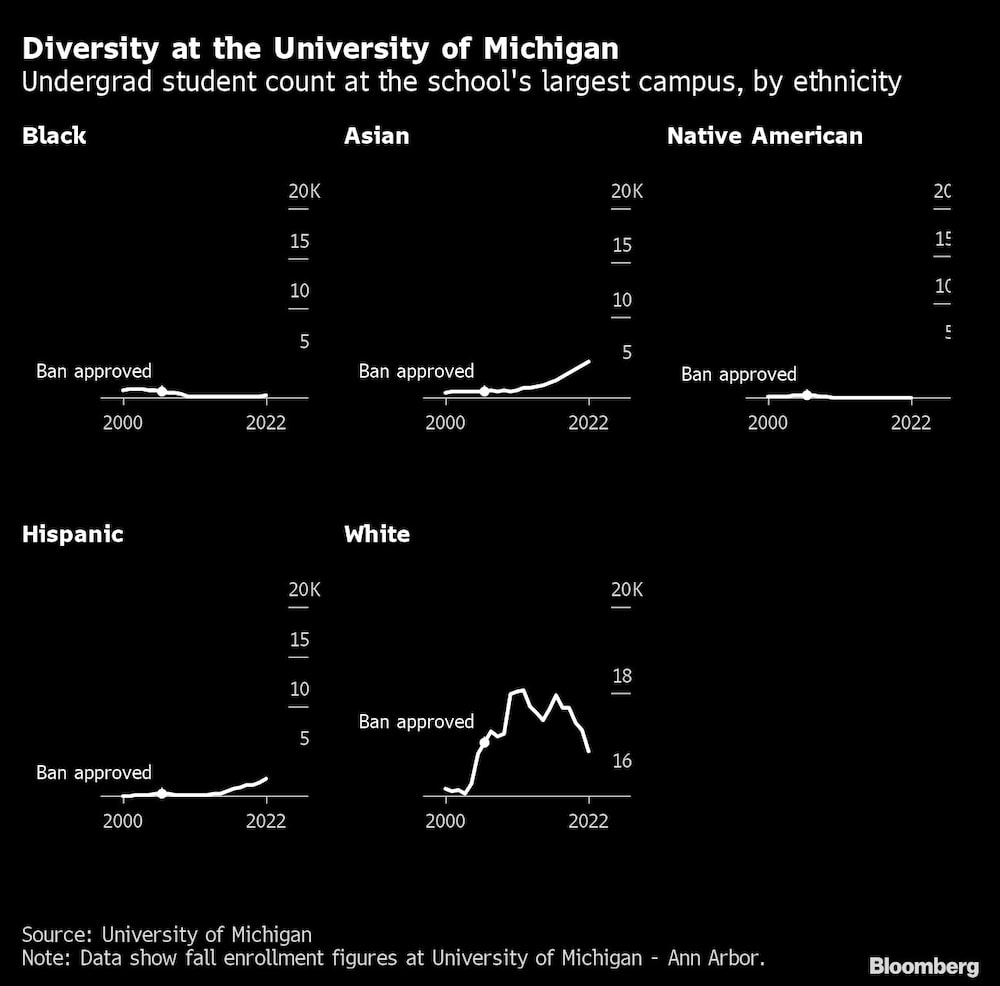

Halfway across the country, the University of Michigan has been employing a large swath of tactics to stop minority enrollment from backsliding since a 2006 affirmative-action ban went into effect. These include considering socioeconomic status in admissions, maintaining an office in Detroit to recruit local high school students and encouraging current attendees to reach out to admitted minority students. The school has also reduced the number of kids it admits early and tried to minimize tuition increases.

But despite spending over 15 years working on these efforts, “race-neutral admissions policies have not significantly increased enrollment of underrepresented minorities,” the school wrote in a 36-page filing to the Supreme Court.

In 2006, the last year before the ban of race-based admissions went into effect, 13% of the schools undergrads were underrepresented minorities. By 2014, minorities made up 11% of students. It wasn’t until 2021 when the share of non-White students reached 13% again.

The change has been particularly bad for Black and Native American student enrollment, according to the school. In 2006, Black students made up 7% of the student body; that has since declined to 4% — in a state where 17% of public high school students are Black. At its largest campus, there were 240 Native American students enrolled in the fall of 2006. By this fall, there were just 40.

“These institutions that aren’t able to carefully consider race in admissions are falling short even as the country becomes more diverse,” said Paulette Granberry Russell, president of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education.

Some schools say they don’t need affirmative action at all. In a court filing in the UNC Supreme Court case, the University of Oklahoma argued schools that don’t consider race are “no less diverse than comparable universities” that do. The university said there has been “no long-term severe decline in minority admissions” since Oklahomans voted for an affirmative action ban in 2012. Enrollments in the University of Oklahoma system for Black, Hispanic and Native American freshman were up overall.

At Norman Campus, the state’s most prestigious and largest campus, though, the picture was more mixed. The number of Black and Indigenous freshmen students fell right after the ban, and Hispanic freshman saw a drop the following year. Percentages of Black and Hispanic freshmen have rebounded, but figures for Native American students remain below where they were. None of the groups have kept up with the state’s increasingly diverse pool of high-school graduates.

Over the years, colleges in these states have adopted other tactics hoping to boost campus diversity. Some have tried targeting lower-income students given that studies find White Americans have six times more wealth than Black ones, or stepped up recruiting at more racially diverse high schools.

Others have ditched standardized-test requirements, as students from wealthier backgrounds tend to perform better on the exams. Others have made it optional, which a 2021 Vanderbilt University study found contributed to a 10 to 12% increase in first-time students from underrepresented racial backgrounds.

Another popular strategy, used by public schools in both California and Texas, is admitting the top performers from every high school in the state. That system, while race-neutral on the surface, guarantees slots to students at predominantly Hispanic and Black schools and those from low-income neighborhoods. (In 2016 the Supreme Court ruled that the University of Texas could use race-conscious admissions to supplement its automatic-admissions rule.)

Schools can also consider dropping legacy admissions, like Amherst College announced it would do last year. A recent study by the American Sociological Association found that legacy admits are not more qualified or better students and tend to be less racially diverse than non-legacies. Their parents tend to be wealthier and in a better position to donate to the institution.

Going to an elite school isn’t the only route to economic security in the US, and increasingly employers are looking outside the most selective institutions for hiring. But it’s still a common pathway to power.

Take the US Supreme Court — the nation’s most powerful judicial body — as an example. Of the nine justices, seven received undergraduate degrees from Ivy League schools, and only one got a law degree from somewhere other than Harvard or Yale.

--With assistance from Greg Stohr

Read more on Bloomberg.com