Bloomberg — As Goldman Sachs Group Inc. boss David Solomon chatted at a November dinner for retired partners, he mentioned that the firm will be among the country’s most profitable big public companies this year. But the veteran mergers banker Geoff Boisi was struck by how muted the excitement has been.

“I don’t know if malaise is the right word — it’s this uncomfortable feeling,” said Boisi, who left Goldman in the 1990s, became a vice chairman of JPMorgan Chase & Co., and has run his own firm, Roundtable Investment Partners. “People are more unsettled and ill at ease.”

He wasn’t just speaking about the mood that night at The Shed, a $475 million arts center in Manhattan’s Hudson Yards.

The biggest U.S. banks are putting finishing touches on their most profitable year ever and preparing to dole out some massive bonuses, yet the usual sounds of Wall Street’s backslapping and toasts have faded. They’re not only hushed by exhaustion from nearly two years of global pandemic, or even wariness of conspicuous consumption in an age of vast inequality. Industry denizens describe a sense that assignments are unending, trouble is brewing and the real fun is elsewhere.

Veterans of past Wall Street booms suggest that, somehow, this one doesn’t feel so good. One reason: The wealth reeled in by elite traders and dealmakers is getting outshined by the quick riches touted by cryptocurrency fanatics, fintech whizzes and meme stocks. There’s also the gnawing realization that the financial industry is benefiting from the turmoil set off by Covid-19, stimulus efforts and a burst of market ebullience that will inevitably fade.

Here’s how prominent investor J. Christopher Flowers puts it: Wall Street knows much of its windfall is coming from “speculative nonsense.” Take, for example, the glut of special purpose acquisition companies — or SPACs — making executives and some bankers rich as they rush to market. They have “a large element of baloney,” said Flowers, the former head of Goldman’s financial institutions group who now runs private equity firm J.C. Flowers & Co.

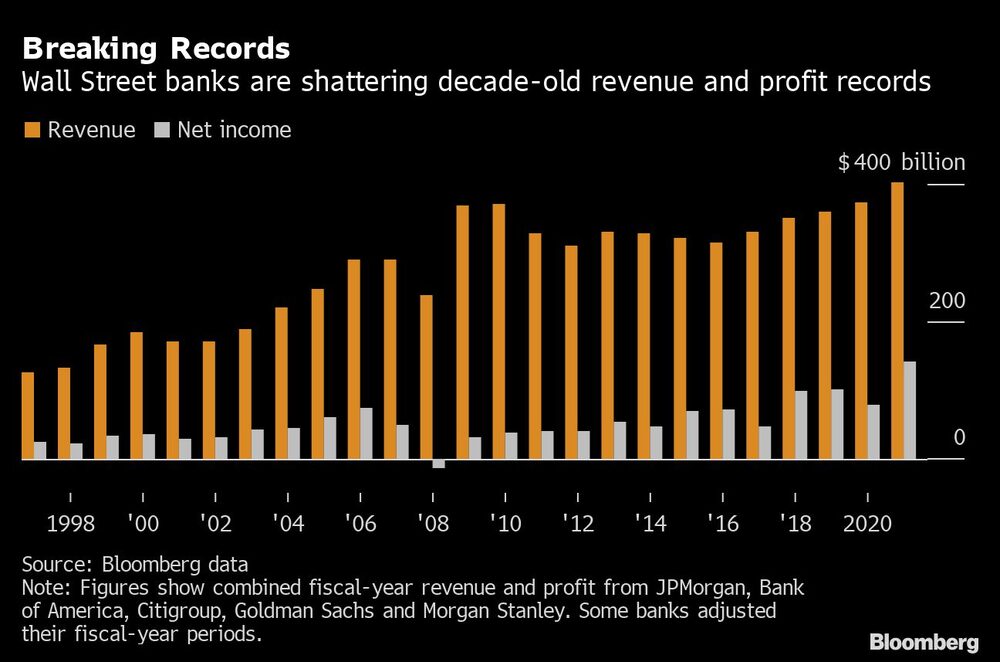

Banks have been toppling their old records this year in almost slapstick fashion.

Banking’s Big Bonuses

Morgan Stanley, which averaged about $3 billion of profit annually during James Gorman’s first half-decade running the firm, made more than $4 billion in this year’s first quarter. Goldman Sachs broke its annual profit record around Labor Day. JPMorgan, which hadn’t pulled in $25 billion until 2018, is on track for about $45 billion. For their work, some bankers, especially those handling mergers and acquisitions, may see bonuses soar.

But it’s not what you have, it’s how much more you have than everyone else.

The founders of Meta Platforms Inc. — formerly known as Facebook — and Tesla Inc., which were barely up and running during Wall Street’s pre-crisis boom, are alone worth more than Citigroup Inc., once the country’s most valuable bank. The packages that JPMorgan and Goldman rolled out for their chief executives may end up being a fraction of what KKR & Co. and Apollo Global Management Inc. will give their bosses. And newbies trading crypto and meme stocks have flaunted the Lamborghinis they’re buying with their new fortunes.

“There’s always somebody doing better than you,” said Mark Gorton, the founder and chairman of high-frequency trading firm Tower Research Capital. The number of teenagers worth $20 million because they giddily loaded up on crypto can be hard on the ego. “Everyone compares themselves to those people,” Gorton added. “I kind of consciously try not to.”

That envy marks a shift from only about a year ago, when Sam Peurifoy sensed colleagues at Goldman were treating crypto as “kind of a cute, niche curiosity.” Known for his gaming persona Das Kapitalist, Peurifoy left around June for Floating Point Group, which provides services for trading digital currency, and is now an executive at Hivemind, a $1.5 billion crypto fund. Despite bankers’ windfall year, Peurifoy said there’s a “feeling in the air that they are missing out,” describing it not as a bleakness but “this overwhelming ‘Wow.’”

Culture of Wall Street

One problem, suggested veteran dealmaker Valerie Red-Horse Mohl, is that bankers focus on net-worth rather than meaning.

“We’ve lacked a sense of community engagement and sustainability on Wall Street for over a century,” said Red-Horse Mohl, who’s now chief financial officer of East Bay Community Foundation. Finance executives know subconsciously that widening inequality is a crisis, she said, and “it cannot keep getting worse.”

This year started on a sour note for many bankers. After a wildly profitable 2020, banks were restrained with their year-end bonuses. Turnover was rising by midyear, firms raced to fill in holes left by the people who’d jumped ship, and the talk turned in the fall to a fight for talent.

At the Goldman dinner, retired executives were happy to see each other. But some worried about rising real estate prices in Aspen and frothy markets everywhere, Boisi said. His mind turned to the trillions of dollars the Federal Reserve has deployed to buoy asset prices. “You don’t know when the piper has to be paid, but the piper has always got to be paid,” he said. “It comes in an unexpected way, and it comes violently.”

There are other forces at play in Wall Streeters’ greyish mood.

George Walker, who runs Neuberger Berman, points to the “huge workloads” facing bankers as markets roar. Finance bosses are uncertain about hybrid work and putting in “extra efforts” as clients focus on environmental, social and governance issues. “Add a little Covid-stress and you don’t have a recipe for glee.”

Some bankers are keeping quiet out of politeness, said Bill Harts, a private equity investor who has worked for Bank of America Corp., Nasdaq Inc. and the venture capital firm Bessemer Venture Partners.

“Because of the pandemic, people don’t want to come off as sounding like, ‘Look at how much money I made while hundreds of thousands of people were dying,’” he said.

Dan Neidich, a former Goldman management committee member, thinks the combination of Covid and political dysfunction is enough to dull the mood on Wall Street. Yet the head of Dune Real Estate Partners predicts bankers will brighten up when they land their bonuses.

“My guess is people will be paid pretty well, and they’ll feel better in January or February than they do today,” he said.

Jon Sobel, another former partner at the bank, isn’t so sure. Unlike in Wall Street’s prior golden eras, a greater share of pay comes with strings attached. Since the global financial crisis, the thinking has been that one way to stop bankers from taking absurd risks and leaving before the cracks appear is to reward them with stock that can take years to vest.

“Nobody’s going to shed a tear for these successful earners,” he said. “But, if you’re one of them, it just doesn’t feel as good as it once did.”