Bloomberg Opinion — Over nearly two years, as Covid-19 has kept people away from movie theaters and in front of their TVs, the economics of Hollywood have been transformed. Digital streaming apps have displaced the box office, and that in turn is changing how everyone in the business gets paid — even stars in the wealthiest reaches of show business.

The shift hasn’t always gone smoothly. Last summer, one of film’s biggest actors, Scarlett Johansson, fought back — and in the process offered a glimpse of streaming’s drastic financial impact.

July 9 was to be the much-delayed date when movie-theater audiences would get to see Johansson play Natasha Romanoff, the Black Widow — only the second female superhero in Disney’s Marvel franchise to get her own film. The star had spent months training for her combat scenes because while other Avengers characters possess superpowers that can be easily fudged through special effects, Black Widow does not. And this was fitting, given Johansson’s personal predicament as a woman in Hollywood, needing to fight harder than a man for fair treatment and pay.

She had received $20 million upfront for the movie but stood to earn another sizable chunk from cinema tickets, or what’s known as back-end compensation, once “Black Widow” debuted. However, Walt Disney Co., Marvel’s corporate parent, decided to also stream the movie on its Disney+ app that same day. This slashed both Johansson’s back-end earnings and Disney’s box-office sales. But it boosted the company’s streaming subscriptions — which is the metric its shareholders now care about most.

The effect, as Johansson’s team painted it, was to rob the film’s heroine of as much as $50 million and instead enrich Disney, a $273 billion company, and its chief executive officer, Bob Chapek.

When Johansson sued, Disney insinuated she was being selfish for thinking of money during a global health crisis. Hollywood women’s groups called this a misogynist attack. And soon afterward, Johansson gave birth to a baby boy. For Disney, the optics were terrible: It had appeared to stiff a star feminist icon and then turn around and insult her.

Or at least that was one way of looking at it. Through another lens, Disney’s decision wasn’t greedy so much as pragmatic. Consider that when “Black Widow” was released, vaccines were only just rolling out and people were still hesitant about watching movies with strangers in the confined space of a theater. What’s more, they were enjoying streaming new movies at home — an option that rival studio Warner Bros. was already providing to HBO Max customers. A cinema-only debut of “Black Widow” in this environment probably wouldn’t have drawn the box-office attendance that could have earned Johansson — the highest-paid actress of the before times — that $50 million payday.

Disney and Johansson eventually settled for an undisclosed sum, but their imbroglio captures a tension that has been slicing through Hollywood as streaming takes over. It’s pitting powerful companies against top actors, filmmakers, talent agents and production-set workers — so far spurring a lawsuit, an agency merger, plenty of heated closed-door negotiations and nearly a catastrophic union strike. Overworked crews are becoming more vocal about their grueling working conditions.

An insatiable demand for streaming content has rather suddenly come face to face with the Covid-19 pandemic, a labor revival and a movie industry still reeling from its #MeToo repercussions. One thing seems certain: Streaming will forever change the way everyone in Hollywood gets paid. Fading movie theaters mean that stars’ bonuses may soon hinge not on ticket sales but on how many subscribers sign up and other unconventional performance measures informed by social-media platforms such as TikTok. And increasingly, power over these financial arrangements is shifting from the iconic studios that once defined Hollywood to a handful of companies mostly in the technology world, including Amazon.com Inc., Apple Inc. and Netflix Inc.

New Data Rituals

At film studios, until the pandemic came along, Monday mornings centered on the high-strung ritual of taking in the weekend’s box-office results and news coverage. Now, in the age of Netflix, Mondays are just another day of poring over viewership data and keeping score of streaming-app sign-ups and retention rates. The entertainment business has taken on an obsession with data more familiar to the tech sphere, and this has spread to shareholders, too, in how they evaluate quarterly corporate earnings.

These dynamics were on display at Disney last month, when its stock dipped 7% in one day — a large drop for a company its size. Since early July, the same month as the “Black Widow” debut, it had added only 2.1 million Disney+ subscribers, compared with more than 12 million in the prior quarter. Investors cared little that Disney’s theme parks and cruise line were now recovering from Covid shutdowns, a sign the company stands to return to earning some $6 billion a year from vacations and merchandise. Shareholders instead focused on the one product that doesn’t yet make money.

Why is the industry so enthusiastic about a market that so far produces, at its best, razor-thin margins? One longtime studio boss said it’s simple: Businesses like predictability. If a studio keeps splurging on programming, customers will keep paying $8 a month — or $15 or whatever the rate is — into perpetuity, which translates into tens of billions of dollars a year. Subscription income is more reliable than taking a chance on a film at the weekend box office. On streaming apps, flops never make front-page news. Studios may not get a giant payday when a movie hits big, but they never have to blow millions promoting one that doesn’t.

WarnerMedia, the AT&T Inc. unit that will soon be sold to Discovery Inc., put its entire Warner Bros. theatrical slate for 2021 on the HBO Max app. Needless to say, star actors including Gal Gadot of “Wonder Woman 1984″ weren’t happy about the sudden shift to streaming, although WarnerMedia managed to keep the wrangling quiet and out of court. And its plan worked: Often when its big movies hit, downloads of the HBO Max app spike, Apptopia data show. Even when films disappoint — “Those Who Wish Me Dead” with Angelina Jolie scored only 62% on Rotten Tomatoes — the streamers at home paying a monthly fee are less bothered than a family that drives to a theater and shells out for tickets, popcorn and soda.

And this emboldens studios to be more creative. “With streaming, the hits-to-misses ratio is probably the same, but you aren’t annihilated for your losses because they kind of go undiscussed, and you’re more celebrated for your hits,” said Todd Garner, a producer and former Disney executive who has worked on recent films such as “Mortal Kombat,” which went to theaters and HBO Max, and “Vacation Friends” for Hulu. “That just makes you want to take more risks, which is good for Hollywood and good for movie fans.” Garner points to the originality of the recent Netflix sensation “Squid Game” compared with the relatively safer bets other legacy Hollywood giants are making.

This isn’t to say there will be no more Marvel blockbusters on the IMAX big screen. Even the unfortunately timed “Black Widow” sold $380 million worth of cinema tickets globally. Disney’s cut was enough to cover its $200 million in production costs. (By August, the company had reaped an additional $125 million from streamers who paid the digital access fee.)

But the world will probably never fully return to theaters. In the U.S., visitations had been falling years before Covid. While many studio bosses and filmmakers still yearn for that Monday morning headline glory, they’re paying at least as much attention to the subscriptions that now drive the industry. They’ve come to accept that even stellar box-office results can’t compete with the one thing that moves a company’s stock price.

Pay-Per-Meme

While streaming is creating big paydays for shareholders, it’s complicating matters for actors. Back in the day (before Covid), a sought-after actor might have been paid, for one movie, $10 million with a promise of 10% of the profits from DVD sales, premium cable-channel showings and other licensing agreements. When a film is made exclusively for a streaming app, there are no such back-end revenue streams for actors.

To avoid Johansson’s experience, stars are beginning to demand a guaranteed fee in case a studio decides to move up the digital release date, according to one producer involved in pay negotiations. Ideally for the actors, this fee rises for each day that streaming infringes on the film’s theater run.

Some stars have the leverage to negotiate even more creatively. As streaming takes over, they could demand to be paid for their ability to drive social-media interest in a movie or series, which in turn drives subscriptions. That’s allowing tech-related companies to play a bigger role in Hollywood than they ever had before, tracking streaming data and developing measurements that could inform such compensation discussions. Parrot Analytics, for one, is working on a way to gauge how fan memes and TikTok videos translate into demand for streaming services.

To illustrate how that could work for various actors, Parrot was asked to compare data for Johansson, an established film star, and Penn Badgley, who’s risen to fame by playing the lead role as the serial killer in the Netflix sensation “You.” Parrot found that Johansson’s online demand is strong year-round regardless of whether she has a new movie, while Badgley’s is tied to his show.

In the 12 months through Oct. 26, Johansson ranked among the top 10 actresses in the U.S., with more than 27 times the average demand of all female actors in the country — slightly higher than Kaley Cuoco (star of the 2020 HBO Max series “The Flight Attendant”), according to Parrot. Johansson might rank higher still if she were more active on social media — like her Marvel colleague Zendaya, who has a young, social-media-savvy fan base. A tweet from either of them would be incredibly valuable to a studio, and they wouldn’t be the first actors to use that leverage. Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson reportedly charged a $1 million social-media fee to promote his film “Red Notice” on Twitter and Facebook.

As for the lesser-known Badgley, when season three of “You” was released in October, his demand temporarily surged — from the high 3,000s on Parrot’s ranking to the top 10. The kind of social-media activity that his character inspires indirectly benefits Netflix, and so it wouldn’t be unreasonable for an actor to ask to be compensated for that as well.

Behind the Camera

The shift to streaming may hinder producers’ and actors’ ability to ride a single hit movie to mega-riches. As one producer put it to me, they’ll have to settle for only sort of rich. But now, with so much streaming content in the works, there’s more work to go around.

For below-the-line crew members who get paid relatively meager daily or hourly wages, that’s both a blessing and a curse. Jobs may be more plentiful, but there’s pressure to speed up productions as studios race to make more content, especially for streaming. And the pay has not kept up with the greater job demands.

“Telling people ‘It’s not a great rate, but this project could really go somewhere’ doesn’t help them pay their bills,” said Isa Gueye, an assistant director and aspiring production supervisor living in Brooklyn who works on indie sets. “There’s a strong element of delusion there. Asking people to work over 16 hours a day and missing meals” — even when penalties are paid to workers for that — “is unreasonable,” she said.

In October, a strike by a large entertainment union was averted — a matter that was anxiously followed not just by the 150,000 members of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees but also by non-unionized industry workers like Gueye who often see the effects of union agreements trickle down to them. Given IATSE’s size, a walkout stood to cripple the industry just as it was restarting work that had been halted by the pandemic.

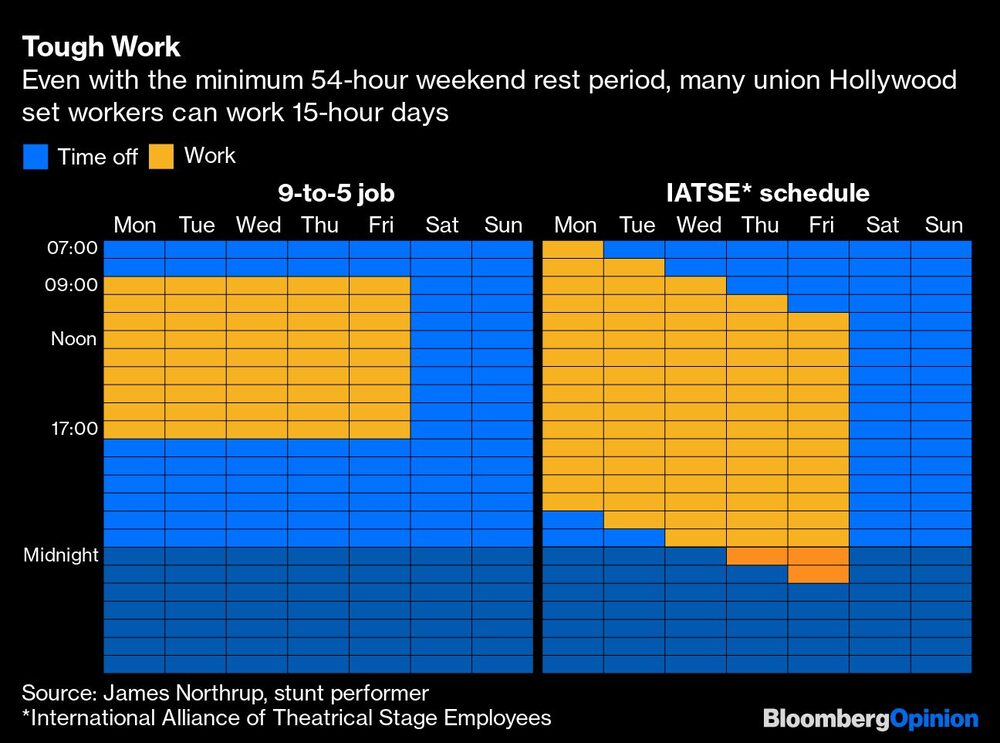

One concession made to union members is a minimum 54-hour weekend rest period. Stunt performer James Northrup — for whom getting lit on fire or hit by a car is part of the job — posted a series of eye-opening spreadsheets that were shared around Instagram showing just how taxing even that schedule can be compared with an ordinary 9-to-5 job:

A worker might be given just 10 hours of “turnaround” time to commute home, eat dinner, sleep and attend to any family needs before having to report back. Production might wrap after midnight on the sixth day, leaving a truncated weekend to catch up on rest and everything else. “I don’t think most of those crew people get enough sleep,” said Northrup, whose wife is a costume tailor and IATSE member. “They’re burned out, and the pandemic doesn’t help.” Exhaustion and a hectic pace also don’t pair well with safety. “When you rush, bad things happen,” he said.

(It was just days after IATSE reached its agreement with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, on Oct. 21, that actor Alec Baldwin fired a prop gun on a movie set, fatally wounding cinematographer Halyna Hutchins and injuring director Joel Souza. This episode galvanized Hollywood workers to call new attention to set conditions.)

As streaming increasingly exerts its influence over Hollywood economics, studios will need to manage the new pressures without endangering workers — even as they come up with a new standard of contracts for actors, directors and other top talent. There may be little sympathy for the highest paid among them, such as Johansson, or concern for how the changing business influences who becomes a film or TV star. But ripple effects are being felt in every corner of the industry. It’s all to keep you, the home viewer, from ever clicking “cancel.”

Keep in mind that this is a change still in progress. The tech business has only just begun disrupting the entertainment world. When it’s all over, Hollywood’s going to be a much different place.

--Lara Williams contributed the “In Demand” and “Tough Work” graphics.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tara Lachapelle is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the business of entertainment and telecommunications, as well as broader deals. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.