Bloomberg Opinion — PolyAI Ltd. is an ambitious startup that creates artificial voices to replace call center operators. Based in London, it has raised $28 million to bring AI-powered customer service to Metro Bank Plc, BP Plc and more. The idea is that instead of the nightmare of dialing random digits in a decision tree, you can instead ask to, say, book a table and a voice — with just the slightest inflection of its machine-learning origins — responds with great civility. That’s nice. But there was a brief moment two years ago when it wasn’t polite at all.

A software developer with PolyAI who was testing the system, asked about booking a table for himself and a Serbian friend. “Yes, we allow children at the restaurant,” the voice bot replied, according to PolyAI founder Nikola Mrksic. Seemingly out of nowhere, the bot was trying make an obnoxious joke about people from Serbia. When it was asked about bringing a Polish friend, it replied, “Yes, but you can’t bring your own booze.”

Mrksic, who is Serbian, admits that the system appeared to think people from Serbia were immature. “Maybe we are,” he says. He told his team to recalibrate the system to prevent it from stereotyping again. Now, he says, the problem has been fixed for good and the bots won’t veer off into anything beyond narrow topics of booking tables and canceling mobile phone subscriptions. But Mrksic also doesn’t know why the bot came out with the answers it did. Perhaps it was because PolyAI’s language model, like many others being used today, was trained by processing millions of conversations on Reddit, the popular forum that sometimes veers into misogyny and general hotheadedness.

Regardless, his team’s discovery also highlights a disconcerting trend in AI: it’s being built with relatively little ethical oversight. In a self-regulated industry that’s taking on greater decision-making roles in our lives, that raises the risk of bias and intrusion — or worse — if AI ever surpasses human intelligence.

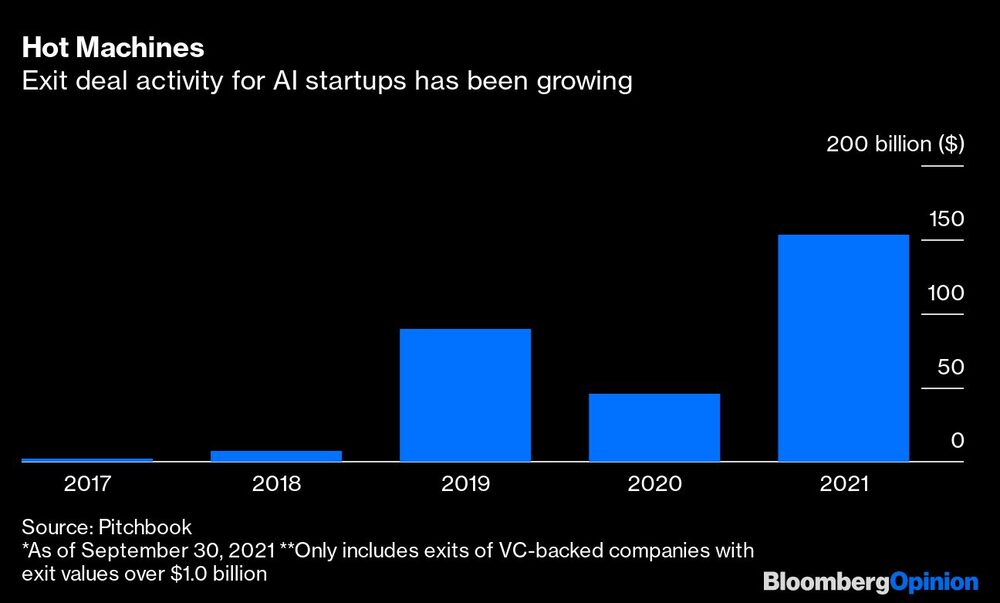

AI systems are finding their way into more applications each year. In 2021, the hot new areas were autonomous vehicles and cyber security, according to a report this week from market research firm Pitchbook, which tracks venture capital deal flows. Future growth areas will be lending analytics, drug discovery and sales and marketing. AI startups are also going public or selling themselves at increasingly high valuations.

After growth faltered in 2019, investors are now seeing outsized returns on AI startups. Globally, they’ve produced $166.2 billion in exit capital so far in 2021, more than tripling disclosed deal values for all of last year, according to Pitchbook. The great allure of AI, the fundamental pitch of investors like Cathie Woods of Ark Invest, is that algorithms are so cheap to implement that their marginal cost over time will be practically zero.

But what if there’s a cost to human wellbeing? How is that measured? And if software designers can’t tell how a chatbot came up with a rude joke, how might they investigate high-stakes systems that crash cars or make bad lending decisions?

One answer is to build in ethical oversight of such systems from the start, like the independent committees used by hospitals and some governments. That would mean more investment in ethics research, which is currently at inadequate levels. A survey published this year by British tech investors Ian Hogarth and Nathan Benaich showed there aren’t enough people working on safety at top AI companies. They queried firms like OpenAI LP, the AI research lab co-founded five years ago by Elon Musk, and typically found just a handful of safety researchers at each company. In May, some of OpenAI’s top researchers in future AI safety also left.

OpenAI and Alphabet Inc.’s AI lab DeepMind are racing to develop artificial general intelligence or AGI, a hypothetical landmark for the day computers surpass humans in broad cognitive abilities — including spatial, numerical, mechanical and verbal skills. Computer scientists who believe that will happen often say the stakes are astronomically high. “If this thing is smarter than us, then how do we know it’s aligned with our goals as a species?” says investor Hogarth.

Another answer for current uses of AI is to train algorithms more carefully by using repositories of clean, unbiased data (and not just pilfering from Reddit). A project called Big Science is training one such language model with the help of 700 volunteer researchers around the world. “We are putting in thousands of hours into curating and filtering data,” says Sasha Luccioni, a researcher scientist at language processing startup Hugging Face Inc. that is helping organize the project, which finishes in May 2022.

That could be an important alternative for companies building chatbots of the future, but it also shouldn’t be left to volunteers to pick up the slack. AI companies big and small must invest in ethics, too.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Parmy Olson is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. She previously reported for the Wall Street Journal and Forbes and is the author of “We Are Anonymous.”