Bloomberg — Arminio Fraga wants to be clear on this point. He does not regret his decision to publicly back Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva’s successful bid this October to return to the presidential palace in Brasilia.

But Fraga, one of Brazil’s most famous investors and an acclaimed former central banker, is not shy about expressing the angst he feels as he watches Lula and his economic team map out a plan to aggressively boost government spending in 2023. That extra cash Lula wants to dole out — some $28 billion in all — to fulfill campaign promises and bolster social welfare programs will stoke consumer demand, he warned, and set back efforts to tame the worst inflation surge the country has seen in two decades.

“I see old ideas that have never worked for us,” Fraga, 65, said in an interview in Rio de Janeiro, where his hedge fund, Gavea Investimentos Ltda, is based.

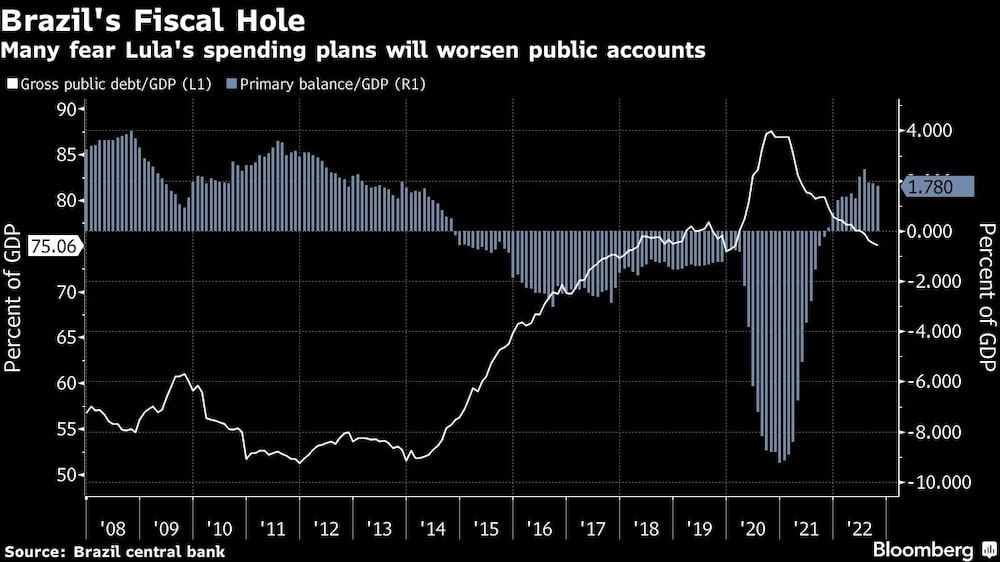

Ahead of taking office on Jan. 1, Lula is seeking congressional approval to raise Brazil’s spending cap, a rule that limits the growth of public expenditures to the inflation rate, by 145 billion reais, or nearly $28 billion. It won’t be the first time the country’s main fiscal anchor is broken. Outgoing President Jair Bolsonaro first did it during the pandemic, and then again this year to improve his re-election chances.

But now, “we’re about to see a massive fiscal expansion in an economy that is no longer in crisis,” Fraga said, expressing concern about the impact of such policies on investor confidence. “Labor markets are getting tight, inflation is high.”

Put bluntly, the incoming administration’s intention to keep injecting stimulus, likely taking the primary budget deficit to nearly 2% of gross domestic product next year, “makes no sense,” he said.

‘Shaky Situation’

Fraga, like many of the nation’s most prominent economists, threw his support behind Lula during a bruising presidential runoff. Concerns about the impact of another four years of Bolsonaro on Brazil’s young democracy united both allies and former critics of the two-term former president.

“It was not an economic call,” said Fraga, who helmed the central bank from 1999 to 2003.

Still, investors have been rattled in recent weeks by the 77-year-old leftist’s picks for his economic team. Fraga’s concerns are in line with a growing sentiment in financial markets that the president-elect’s first steps signal his third term will be one of inflationary spending and greater government intervention in the economy.

Lula’s incoming Finance Minister Fernando Haddad has tried to ease such fears by promising to present a proposal to stabilize debt levels early next year. But with tax revenue likely falling in 2023 along with commodity prices and an expected economic slowdown, Fraga stresses that a comprehensive plan needs to be announced soon.

The new government has little time to get public accounts in order because, with gross public debt running at around 75% of GDP, annual inflation at 5.9% and the key interest rate at 13.75%, Brazil’s fiscal situation is far more fragile than many of its middle-income peers, he said.

“What’s the time frame to turn that deficit into a surplus?” he said. “We can’t just hope for the best.”

Spending concerns were heightened further when Lula appointed Haddad, a former mayor and close ally, as his finance chief, giving him and the new head of national development bank BNDES the task of helping “re-industrialize” the country.

A key fear is that the new government returns to issuing high levels of subsidized credit through state-owned banks. Lenders like BNDES gave out billions of dollars in loans at below-market rates during many administrations, but Lula’s hand-picked successor, Dilma Rousseff, took the practice to new heights causing economic distortions and complicating the work of the central bank.

Fraga said he doesn’t believe such loans would return to similar levels, but any move in that direction would be concerning. At worst, if spending goes unchecked, Lula risks losing more investor confidence and even recession, he said.

Fraga also pointed to economic opportunities for Brazil, like attracting much-needed investment for its out-of-date infrastructure, which would bring in private capital. Reform of the country’s byzantine tax code, which Haddad’s team has pledged to carry out, would also significantly boost growth, he said.

Of course, the jury is still out, and much will depend on how the incoming administration proceeds in the early days.

“This is a shaky situation we’re in,” Fraga said. “There’s no room to maneuver, there’s no safety margin.”

Read more at Bloomberg.com