Bloomberg Markets — One evening in August, Gabriel Boric sat outdoors on a bench, listening and taking notes. A light jacket covered the tattoos on his forearms, but his thick beard and full head of unruly hair betrayed him as the rabble-rousing student protester he was not long ago. In a working-class neighborhood of Santiago, the capital of Chile, he represented the vanguard of a fast-rising left-wing political movement.

At 35 years old, Boric has become the front-runner in the race to become president of Chile. His ascent, part of a broader shift to the left across Latin America, is rattling international corporations and investment firms, which have long favored Chile as perhaps the most market-friendly developing economy in the world.

One of the voters flocking to see Boric that day complained of long waits and poor care at public hospitals. Boric, who can be bookish, looked down, gathering his thoughts. Then he released them, like steam from a kettle. “This has to fill us with rage,” he said, clenching a fist. “And transform that rage into action.”

Rage helps explain why Boric consistently polls at or near the top of the seven candidates vying to lead Chile. It’s rage over inequality, as is evident from the hammer-and-sickle Communist Party flags that flutter nearby in solidarity with his movement, Frente Amplio, or Broad Front. As the name suggests, the rage also derives from something bigger, a growing generational shift in cultural attitudes about gender and sexuality along with economic views on wealth and taxes.

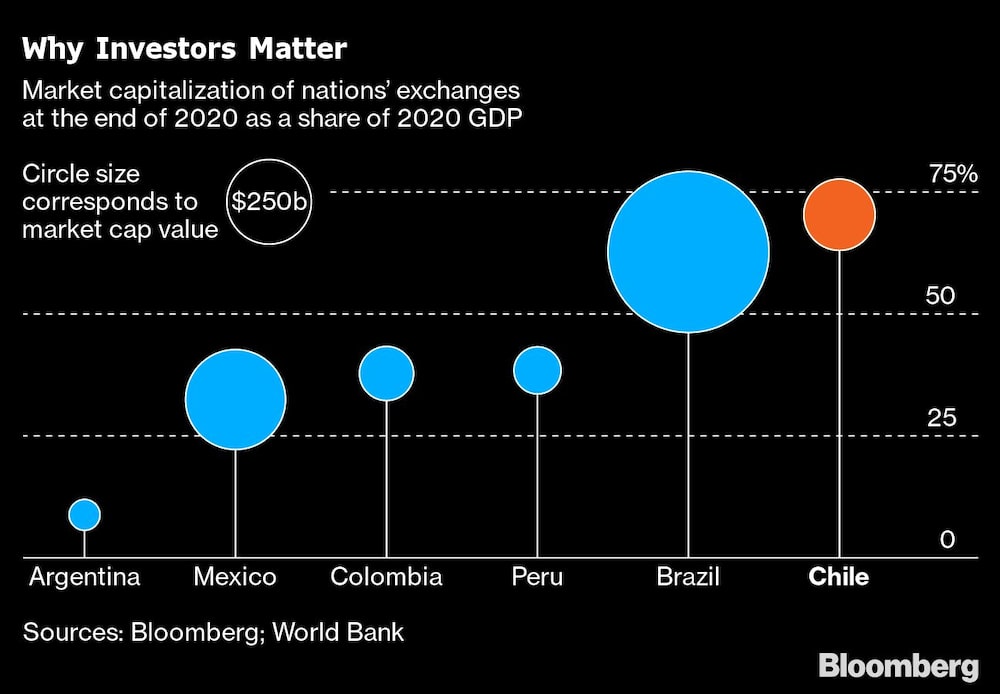

The political choices of the 19 million inhabitants of Chile—a country with a $253 billion gross domestic product, roughly the size of South Carolina’s—have an outsize influence on world commerce. For half a century, Chile has been the poster child for how free markets can spur growth and lift people out of poverty—an approach sometimes described as neoliberalism, a term the left tends to hurl as an epithet.

Chile’s business-friendly climate dates back to the 1970s, when the dictator General Augusto Pinochet reduced trade barriers and slashed regulation to stimulate foreign investment. As Chile turned toward democracy after 1990, courts documented the torture, extrajudicial killings, and other human-rights abuses under Pinochet. Yet his economic approach survived leaders and parties of all political leanings.

Many economists credit these pro-market policies with what has been called the Chilean Miracle. Chile has Latin America’s highest credit rating and attracts more direct foreign investment as a percentage of GDP than such powerhouses as Brazil and Mexico. Chile’s central bank projects that the economy this year will grow as much as 11.5%, more than any developed or emerging-market country tracked by Bloomberg. Chile reigns as the world’s biggest copper producer and a major supplier of lithium, essential for smartphones and electric cars. From 1990 through 2000, average incomes doubled, poverty fell in half, and the country’s stock market soared fourteenfold.

Recent investment results have been less robust, in part because of rising production costs for copper. In gritty neighborhoods where stray dogs fight for scraps next to tire repair shops, Chile’s success story can feel like a cruel joke. Despite years of steady economic growth, the country has one of the biggest gaps between rich and poor among nations in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), whose members are 38 democracies with market-based economies. In other words, much of Chile has benefited little from its status as an investor favorite. Now, Boric and his movement argue that there’s been, in a sense, no change in the country’s economic fabric since the dictatorship.

In late 2019, street demonstrations exploded over a minor increase in public transit prices. Participants trashed major subway stations and demanded changes in national priorities, including the treatment of Indigenous groups, the distribution of water, and the management of pensions.

The Covid-19 pandemic then further exposed, and intensified, societal inequality. In May the country voted for representatives who will rewrite its constitution, left over from the Pinochet dictatorship. Those elected for the task lean heavily left.

Today, in a head-spinning shift, Boric is running to succeed a pillar of neoliberalism: the conservative billionaire Sebastián Piñera, a Harvard-educated economist who made his fortune in credit cards and airlines.

A new generation, bucking the country’s traditional cultural views, dominates public discourse. At the August campaign event, a voter who said he was transgender described violence and discrimination at work and home. Boric recounted a conversation he’d had with a gay Chilean poet and essayist who railed against the strictures of a society that discriminated against people like him.

One of Boric’s closest rivals, center-right candidate Sebastián Sichel, is, like Boric, young and tattooed. The 44-year-old lawyer opposes upending the current economic order. But Sichel favors same-sex marriage and increasing aid to the poor.

Boric’s coalition is calling out economic inequality and supporting gender fluidity, green industries, minority rights, and the creation of a tax-and-spend state where market forces are no longer revered. As Boric has said on more than one occasion, “If Chile was the birthplace of neoliberalism, it will also be its grave.”

With almost 660 million inhabitants and several dozen countries, Latin America can’t be easily categorized. But there are patterns, and it has swung in waves from left to right.

Two decades ago, what’s often described as a pink tide swept into power leftists such as Hugo Chávez in Venezuela and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil. Lula in particular seemed to offer an alternative model for development, fueled by a commodity-price boom and more social spending. Like the market-based approach, it pulled tens of millions from poverty.

Another pink tide now seems to be under way. A likely reason: The right had the bad luck to be in power when Covid crushed the region’s health system and killed more than a million people. Latin America has 8% of the world’s population and 20% of its deaths. In 2020, Latin America’s household wealth per adult dropped 11.4%, more than any other region in the world, according to Credit Suisse Group AG.

The current pink tide swept first into Peru. Pedro Castillo, a rural teacher and union activist from a Marxist party, squeaked past the pro-business candidate on a campaign promise of “no more poor people in a rich country.” Investors ran for the exits, and Peru’s currency plunged more than any other, except Afghanistan’s.

Colombia has elections next year. Its markets-friendly president, Iván Duque, can’t run again because of term limits and is deeply unpopular, posing a challenge for his party’s successor. Leftist Gustavo Petro, who promises a “green economy,” leads the polls.

In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro, a right-wing populist, is expected to face a stiff challenge from ex-President Lula of the previous left-wing wave. The victors in this round will face a tougher challenge than 15 years ago because of empty coffers and steeper government debts.

Some analysts reject the concept of a pink tide, saying it reduces the complexities of countries with their own stories. “Boric is clearly a product of very particular circumstances in Chile,” says Michael Shifter, president of the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington-based policy organization promoting democracy and social equity in Latin America and the Caribbean. “Any comparison with other leaders is difficult. I don’t think he’d be particularly close to Castillo in Peru.”

Much of what Boric is proposing isn’t entirely different from the approach of many European social democracies or even what Democrats are advocating in the U.S. He says he would redistribute wealth to fight poverty and push for workers’ rights, such as mandating shorter workweeks and promoting collective bargaining.

Boric calls for raising taxes on large fortunes and incomes and cracking down on tax evasion. He’s also proposed a levy on mining royalties and “green taxes” on fuel and industrial emissions. Overall he’d raise taxes, as a percentage of GDP, to 29.5% from 21% over the next decade. That would be closer to the 34% average of OECD countries, and 5 percentage points higher than the U.S.

“We need a new model of development,” Boric says during a 45-minute interview via Zoom in August, “where the creation of wealth is not limited to extraction, the distribution of wealth is not based on trickle-down.”

Beatriz Sanchez, a journalist and former Broad Front presidential candidate, says Boric represents a return to the values of Salvador Allende, Chile’s first socialist president, who was elected in 1970 and overthrown by the Pinochet-led military coup three years later. “Allende is someone who marks a path of change and social justice for Boric and the Broad Front,” she says.

This comparison with Allende, who nationalized the copper industry, alarms some businesses, which are already pulling back. Consider Lundin Mining Corp., a publicly traded company based in Toronto with operations around the world. After spending $1 billion upgrading its copper operations in Chile, Lundin is holding off on more.

“We’re going to wait and see before we put too much money into it, and I’m sure everybody else is doing the same,” says Chairman Lukas Lundin. “If there is too much uncertainty in the next year, year and a half, obviously we won’t push the button.”

Australian mining and oil giant BHP Group Plc owns three copper mines in Chile, including Escondida, the world’s biggest. BHP executive Carlos Avila has testified in the Senate against new mining royalties proposed by several left-wing lawmakers, an approach Boric strongly supports. Avila said the levies would derail projects and Chilean mining would be less competitive.

Inmobiliaria Oriente, a family-owned real estate firm, halted two residential projects and a strip mall in the north of Chile and put a commercial center in Santiago on hold. Chief Executive Officer Javier Chadud says Boric’s plans “may affect the local investment environment and make it difficult for us to find new opportunities and clients.”

Wall Street is skittish, too. In June, UBS AG analysts recommended that investors reduce their exposure to Chilean stocks before the November election. In September, Bank of America Corp. suggested no holdings at all. Guido Chamorro, a portfolio manager at Pictet Asset Management in London specializing in emerging-market debt, said Chile’s region-topping credit rating—single-A from S&P Global Ratings—could be at risk. New mining taxes from a leftist government, he says, “would erode the long-standing positive international sentiment that has been built up over many years.”

Boric grew up in Patagonia at Chile’s southern tip, a rugged windswept area of sheep farming and glaciers. A tattoo on one of his forearms represents “a lonely lighthouse” set “among the stormy and mysterious seas of Southern Patagonia,” he once wrote on Instagram. “There I’m going to live one day. But for now, it lives with me.” His invocation of the country’s periphery, rather than the capital, has added to his appeal as an outsider unafraid to take on the moneyed urban elite. His father, who supports the center-left Christian Democrats, is a chemical engineer. Boric attended law school in Santiago. While helping to lead student protests over the cost and quality of education, he was elected president of the student federation.

Boric, who’s unmarried, lives in a Santiago apartment, surrounded by well-worn, graduate-student-style shelving and books. Those volumes, especially works of political science and literature, left an impression on a politician who describes himself as “part of a tradition of the Latin American left.” He cites Alvaro García Linera, a Marxist sociologist and former vice president of Bolivia often described as one of that country’s leading intellectuals. He also has European influences, including the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, known for his theories of how the capitalist class stays in power through cultural hegemony rather than violence. Boric, who speaks fluent English, reads history books on the British welfare state and at times sounds as much like a Northern European social democrat as a Latin American firebrand.

In his view, society has two choices: remedy inequality or devolve into chaos or extinction. “We’ll save ourselves together or sink separately,” he says. “The climate crisis is the best evidence of this, as is the pandemic.”

Boric’s natural allies include supermarket workers on strike at a major grocery chain, demanding better pay and health coverage. “The fact that he’s taken the time to speak about the strike, to draw attention to what’s going on up north, that means he’s very human. That means that, yes, he has the potential to be a great president,” says Priscilla Fernandez, a union official. He also has academics’ support. “You can’t create a new society without changing the economic model,” says Manuel Antonio Garretón, a Chilean sociologist.

But bankers, business leaders, and even some former left-wing government officials are pushing back. Sergio Lehmann, chief economist at Banco de Crédito e Inversiones in Santiago, says Boric’s plans could trim the longer-term annual economic growth rate to about 1%, from 2.5%. René Cortázar, a former minister under the center-left presidencies of Michelle Bachelet and Patricio Aylwin, says higher taxes will drive away investors.

“Neither foreign nor domestic investors are obligated to bring their resources to Chile,” Cortázar wrote in the El Mercurio newspaper. “When they decide where to put their money, they analyze the rules of the game in each country to see where it’s most convenient to go.”

In an interview, Sichel, Boric’s center-right opponent, describes both populism and proposals to overhaul the nation’s economic model as “cancers” that he intends to excise. He’s also condemned the conduct of street protesters, whom Boric supports. “You shouldn’t give up one of the government’s main obligations, which is maintaining order and controlling violence,” he says.

Neither candidate embodies Chile’s extremes. A former social development minister under President Piñera, Sichel’s running as an independent, though representing Piñera’s right-wing coalition, Chile Podemos Más (Chile We Can Do More).

Along with supporting gay marriage, Sichel, like Boric, attacks Chile’s tradition of cultural secrecy that has long hurt the disadvantaged. In an unusual decision for a politician in Chile, he’s spoken openly of his own struggles. He was raised by a single mother, who got pregnant at 17 by a father who disowned them. In a Sábado magazine column, he wrote of his mother’s psychiatric challenges and alcoholism and of living at times without water and electricity. In his late 20s, Sichel searched for his father and met him. In a poll this week, Sichel slipped to No. 3, behind Jose Antonio Kast of the right-wing Republican Party.

For his part, Boric defeated a communist and seeks to distance himself from the socialist policies of Nicolás Maduro, the president of Venezuela. In his view, they’re authoritarian and benefit only the government’s allies. He also wants to reassure international investors.

“Those willing to pursue a model of development that is environmentally sustainable, with good labor practices, and that generates technology transfer and a fairer distribution of wealth will be more than welcome,” he says.

Boric acknowledges the concerns of business leaders that his victory could damage investment in Chile, hurting the economy. “Of course, I’m worried,” he says. “But I believe that everybody understands—even the investors—that if you have a broken society, there are no expectations of having long-term investments. Public faith is lost, and you end up killing the goose that laid the golden egg.” If he wins, he’ll have to solve the riddle of fighting inequality without ending the Chilean miracle.

Thomson is bureau chief for Bloomberg News in Santiago, where Fuentes is a reporter and Malinowski is an editor. Bronner is a senior editor in New York.