Bloomberg — Chile’s record current account deficit will keep the peso (CLP) under pressure long after the central bank’s $25 billion intervention program is done and dusted.

The deficit swelled to 8.5% of gross domestic product in the second quarter, the highest for at least two decades. That was roughly triple the year-earlier figure and represented $6.6 billion leaving the country in just three months.

Not only is that rate of outflow unprecedented this century, it also comes at the worst possible moment as financing costs rise worldwide. With commodity prices subdued amid the threat of a global recession, the only way for Chile to narrow that gap without allowing the peso to slump is by slashing demand, and that means a recession -- potentially a deep one.

Read more about Chile’s dire straits:

“The deficit has reached levels that raise alarm bells,” said Sergio Lehmann, chief economist at Banco de Credito e Inversiones in Santiago. “Excessive spending in 2021, along with a significant reduction in household savings has led to a dangerous widening of the deficit, which should be corrected with urgency.”

The central bank and economists all forecast that the deficit in the current account, which is the broadest measure of trade in goods and services, will narrow next year. The question is, will it shrink quickly enough to stop the peso hitting fresh lows. Chile can’t afford to hemorrhage dollars at this pace for long.

What Bloomberg Economics Says:

“The wide current account deficit implies high external financing needs at a time when financing costs are increasing and financing availability is more constrained. It increases the vulnerability of Chile to changes in external financial conditions and helps explain why the peso continues under weakening pressure.” --Felipe Hernandez, Latin America economist

Hang Over

Chile’s peso hit a record low of 1060.4 to the dollar on July 14, from 823 at the start of June. The subsequent intervention program lifted the peso by as much as 16.9% over the next month, before the news on the current account deficit sent it back down again. The program runs out on Sept. 30.

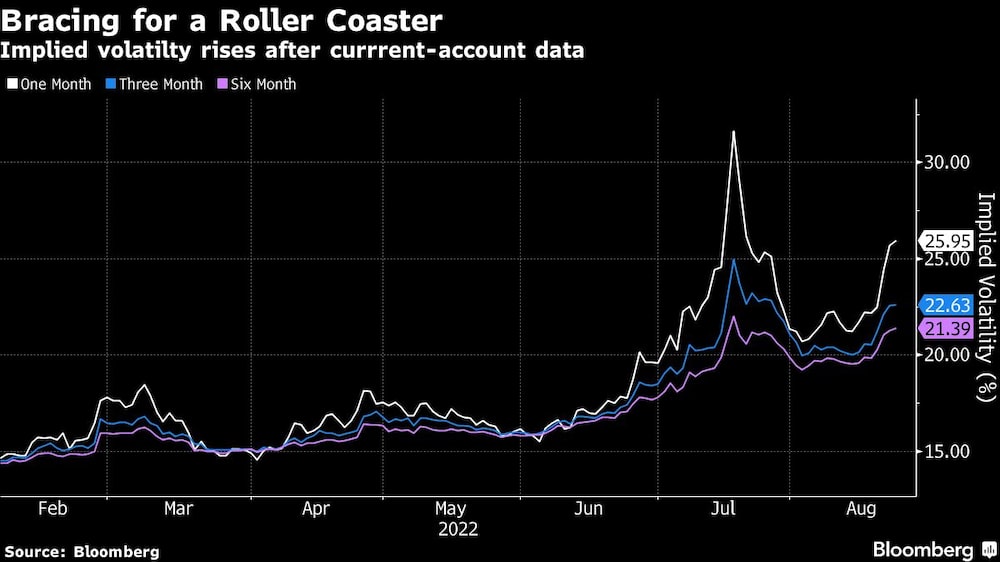

Implied volatility in the peso jumped after the current-account data was published on Thursday.

In many ways, the peso is paying for Chile’s excesses.

During the pandemic the government pumped billions of dollars into the economy in stimulus payments. At the same time, Chileans withdrew about $50 billion early from their pension savings.

The result? A spending frenzy that pushed up retail sales by more than 60% year-on-year for three months in a row mid-2021. That is far more than they ever fell. Now the party is over, and Chile and Chileans have to live within their means again.

“The economy needs to leave behind the current situation of excess spending, and it has started, it has given the first signs,” central bank President Rosanna Costa said at an online event on Monday.

Retail sales have fallen year-on-year for two months in a row after the central bank raised its key interest rate by 9.25 percentage points in 13 months. Following a boom in 2021, import growth has also stalled.

But Chile is going to need a whole lot more pain before the current account becomes sustainable again. The extent of that pain may become clearer on Sept. 6, when the central bank is likely to raise interest rates to attract foreign capital and cut domestic demand. Swaps are pricing in a 75-basis-point hike and a roughly 40% probability of 100 basis points.

The country is already teetering on the brink of a technical recession. Gross domestic product was unchanged in the second quarter after falling in the first, and domestic demand has diminished for two straight quarters.

Wells Fargo expects multiple sovereign credit downgrades over the next 12 months, which should contribute to peso weakness and help USD/CLP reach 1,000 again in 2023, according to a note signed by economists Nick Bennenbroek, Brendan McKenna and Jessica Guo.

And while Costa says the central bank has the reserves and credit lines to protect the peso, depleting those “external buffers should leave the peso more vulnerable to exogenous shock scenarios, as well as less credit-worthy,” the economists wrote.

Read more at Bloomberg.com