Bloomberg Opinion — Call me sentimental, but while everyone was lauding Tesla Inc.’s astonishing rise to a more than $1 trillion market value on Monday, all I could think about was how wretched the rest of the auto industry must feel, and how they might respond.

In just one frenetic trading session, Tesla added $118 billion to its worth, or almost double that of Ford Motor Co.’s entire market capitalization.

The trigger for this latest surge — a deal to supply 100,000 Teslas to Hertz Global Holdings Inc. — is a head-scratcher, as it represents “only” about $4.2 billion of revenue. And arguably it’s not even this year’s most significant car rental deal.

In July, a Volkswagen AG-led consortium said it would acquire Europcar Mobility Group, Europe’s largest car rental operator, for around 2.5 billion euros ($2.9 billion). VW plans to develop Europcar into a “mobility platform,” offering services such as car-sharing and vehicle subscriptions. Europcar already expects that in two years, more than one-third of its fleet will be electric or hybrids. Investors yawned.

Tesla’s U.S. and European rivals have tried every trick in the book to hype their technology chops and rein in Tesla’s stock market lead. Many have copied directly from Elon Musk. They’re rolling out electric models, building battery plants, investing heavily in software and making the sales process more customer-friendly. I expect they’ll continue shaking things up, but so far nothing has made much difference.

In one respect, this double-standard is totally justified: Incumbent automakers took too long to take electric vehicles seriously and Musk seized the advantage.

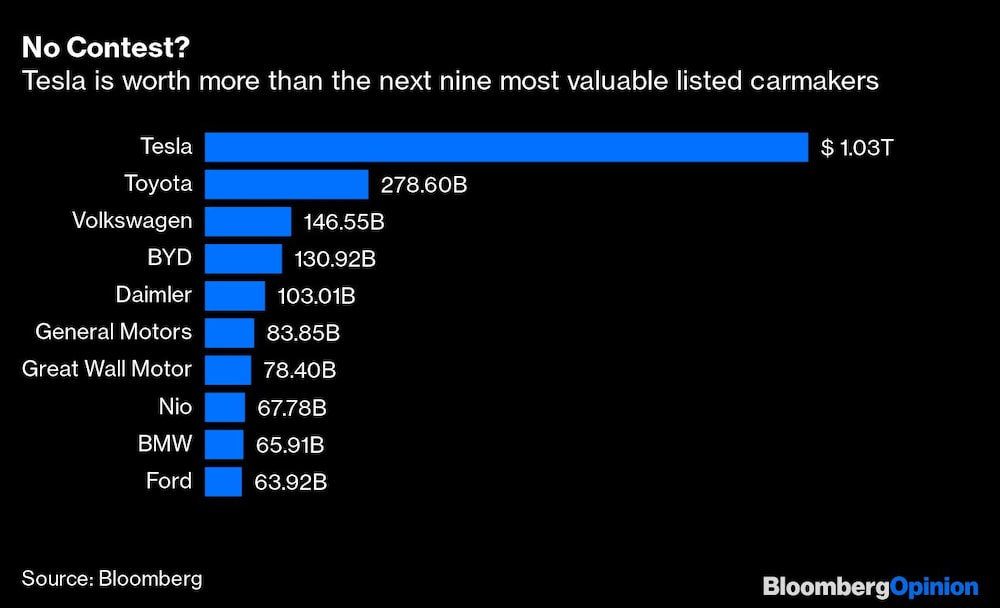

Yet even now that they’ve begun proselytizing for the electric cause, their valuations remain relatively meager. As has been widely noted, Tesla is worth more than the next nine most valuable listed carmakers combined. This is the stock market’s way of telling the laggards to give up, which is odd considering how most of them still make plenty of money.

But Tesla has also become consistently profitable, and if it wanted it could tap its inflated equity to fund plants and technology, as it’s done in the past. In contrast, rivals must fund those investments mainly from their own cash flows.

Volvo Car AB’s recent experience is instructive. On the same day Tesla breached a $1 trillion valuation, the Swedish premium manufacturer was forced to cut the size of its imminent IPO due to lackluster investor demand.

Volvo sold almost 800,000 vehicles in the past 12 months — around the same as Tesla — and though its electric volumes are currently modest, it’s vowed that by 2025 half of its sales will be electric and by 2030 they all will be. It also owns a nearly 50% stake in Polestar, an impressive all-electric startup. Yet Volvo is set be valued at less than $20 billion when its shares begin trading on Friday, around 50 times less than Tesla.

There’ve been times during the past year when it seemed the incumbents might regain an advantage, but any momentum they’ve enjoyed has tended to be modest or fleeting.

Ford and Daimler AG are among those that have discovered Tesla-esque technology events are a good way to emphasize their electric commitments and fire up their own shares. Just last week VW held an investor event to highlight the value of its Lamborghini luxury sportscar unit.

Spinoffs are another increasingly popular tool to tackle the valuation gap. Daimler is listing its heavy trucks unit, and there’s speculation VW may do the same with its highly profitable Porsche unit — I’ve argued before that this would be a no-brainer.

Even better is listing a purely electric business, ideally in the U.S. where tech valuations tend to be more “aspirational.” Polestar’s recent SPAC deal valued it at $20 billion, which is more than co-owner Volvo is expected to be worth. Unfortunately, it’s difficult for most carmakers to carve out their electric activities because these are too bound up with their residual combustion engine units.

No wonder some have resorted to a simple name-change: Germany’s luxury leader is ditching “Daimler AG” for the sexier Mercedes-Benz. And while Volkswagen was only kidding about becoming “Voltswagen,” maybe it should seriously consider the idea: The April Fool’s gimmick briefly turned it into a meme stock. VW Chief Executive Officer Herbert Diess has now learned how to use social media, and a budding friendship with Musk, to his company’s advantage.

None of these efforts, though, have been enough. Musk continues to flaunt his lead: Tesla recently threw a huge party at its new plant near Berlin — the openness and frivolity made the German auto industry seem even more dour by comparison. Tesla has also coped admirably with the industry’s semiconductor shortages, and its gross margins are increasingly impressive.

Unless the company slips up, it looks like legacy producers will have to live with their stock-market impediment. Copying the best elements of Tesla’s approach remains the only path to salvation. But don’t count on being rewarded much for it.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.